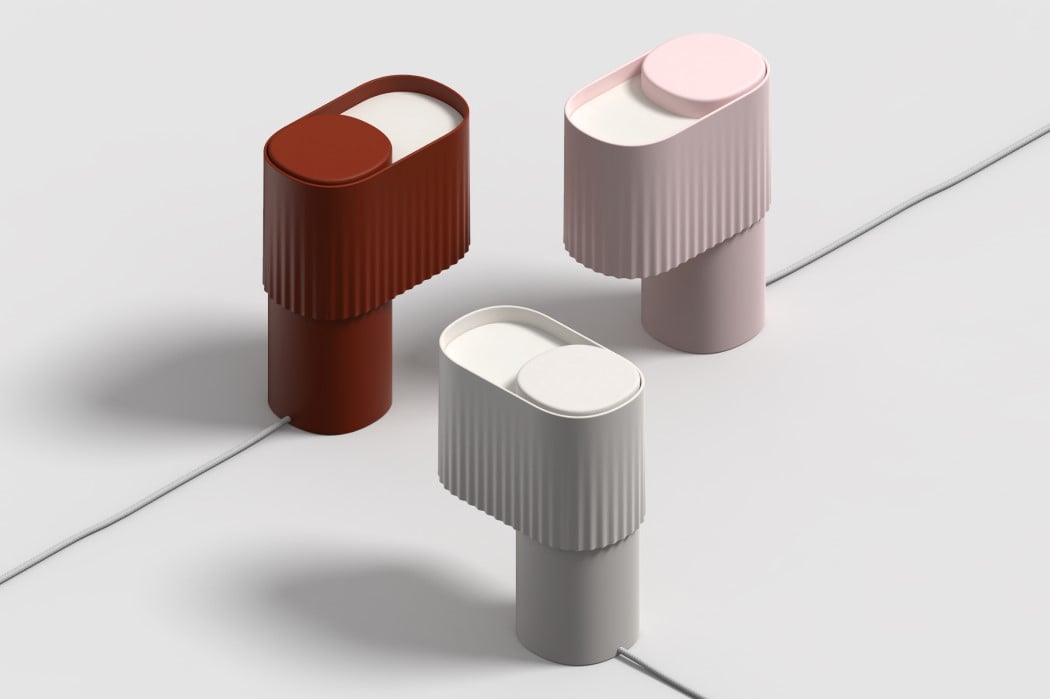

Sam Gwilt started his fledgling YouTube channel to capture his journey as a designer. Over time, that YouTube channel helped build a community that, along with Sam, ‘does design’. Sam’s channel ‘Sam Does Design’ hosts a variety of videos, from sketching and rendering tutorials, to Q&A’s to even portfolio reviews, and has helped Sam build a strong audience/community of designers and design students. Sam recently designed a lamp, titled The Weight, for Gantri, an online studio that partners with designers to create modern-day lighting designs exclusively using 3D printing. The Weight plays on the word ‘light’ and creates a visual contrast by being the opposite… heavy. Designed to look like an orb that weighs down on a platform, causing it to visually deform, The Weight is entirely 3D printed (and is actually quite lightweight). Its soft design (and soft lighting) instantly adds a touch of playfulness to a room while also lighting the space up with a soft glow.

We got a chance to sit down with Sam and talk to him about The Weight, the design process behind it, his YouTube channel, and got him to share some portfolio tips with us. We even asked him about the can of San Pellegrino that went viral on his Instagram page!

Yanko Design: Hi Sam! Tell us about yourself and how you came to ‘do design’

Sam Gwilt: “Hey I’m Sam and I do design!” I’ve been interested in design for as long as I can remember. One side of my family are engineers, the other side artists, so I’ve always had a deep appreciation for both disciplines. Luckily for me, there was a technology college close to my childhood home. That was where my first lessons in design were taught, which laid the foundations for my career without me even knowing.

I studied industrial design at Brunel University London where, alongside my studies, I gained two years of industry experience. That was how I managed to get my foot in the door and secured my current job at Precipice Design. I also worked with Made in Brunel as a Social Media Manager. I was part of the student-led programme that connects students with industry and organises the design events throughout the year. I used the skills I learned there to help run Sam Does Design, which in turn helps to teach others.

YD: You recently designed a lamp in partnership with Gantri. Do tell us more about the ‘Weight Lamp’.

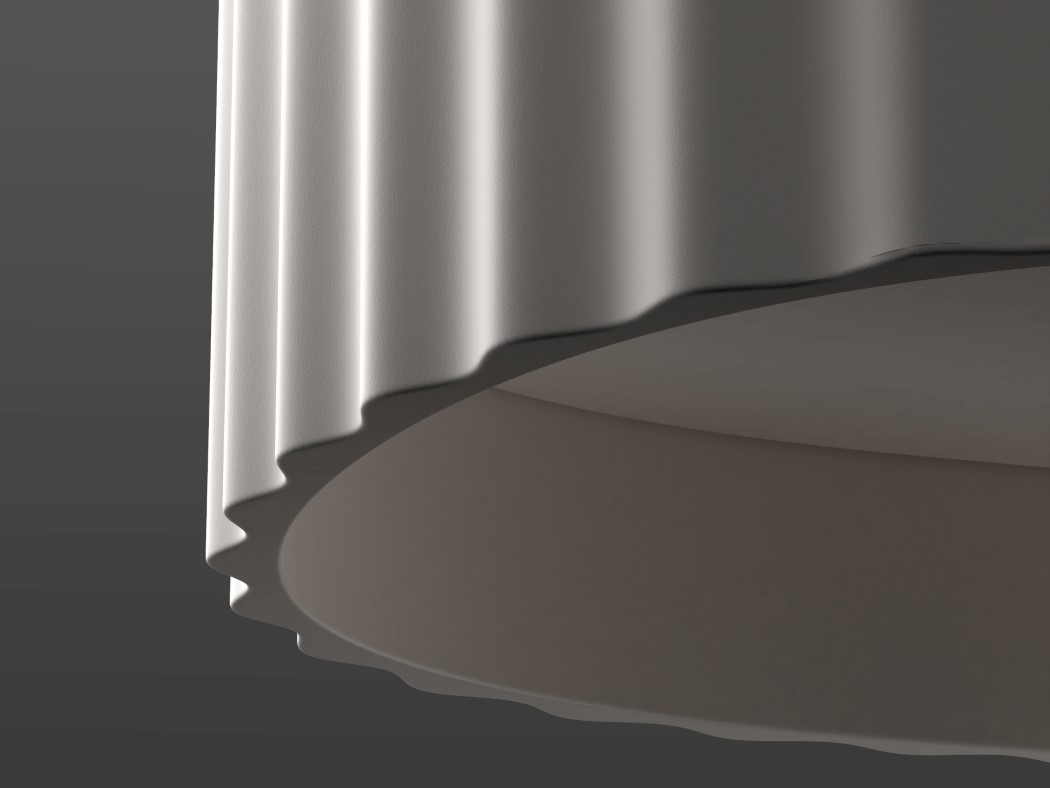

SG: Weight is an ambient light with a 360-degree glow. It was designed specifically for 3D printing and is made from a corn-based polymer. I wanted to play with the concept of weight and mass; how heavy could I make light seem? The 3D printing process means that plastic becomes molten as the product is made, and I wanted to capture that aspect of the process. The intention was to make the final form seem soft and malleable. The sphere appears to have fallen onto the base and has deformed the shape, where it now seems suspended in time.

YD: How did this collaboration with Gantri come about?

SG: I posted a separate concept design to my Instagram page, and I saw a comment that said: “this looks like a design for Gantri”. That was the first time I’d heard about them, so I checked out their website and was really impressed by their process and existing designs, and eager to find out if there was a way I could work with them. I reached out to see if they were looking for new designers and the stars must have aligned because the timing was perfect. After chatting with the team at Gantri, I began working on the concept about a month later.

YD: So, what was the design brief? And how long did it take to go from idea to final product?

SG: The brief was refreshingly open to interpretation. Gantri has an amazing in-house design and engineering team but the big-picture concept and specific scenario were up to me to define. I presented three completely different concept routes that I thought could be interesting, and we decided to develop the strongest one based on how easy it was for potential customers to understand the concept at first glance. It was important for the product to be understood without needing to be explained with any sales copy. I had ideas that explored aspects other than weight but still kept surface and material exploration as a theme, and I hope to revisit those designs in the future. I’d love to work with Gantri again: their streamlined design process and fast prototype turnaround meant that from concept to sale took around three months.

YD: The Weight lamp is designed specifically for 3D printing. How different is that from designing for injection or blow molding?

SG: No draft angles! The geometric design lends itself to 3D printing as nothing needs to be de-moulded. That meant that all sides could be geometrically perfect. The flip side is not being able to print past 45 degrees due to printer constraints, but some clever engineering and internal structures meant that the cylinder base prints perfectly every time. Another benefit was working on the whole product without the need for split lines or multiple parts. It’s a sad moment when a split line needs to interrupt a nice clean surface due to pesky manufacturing constraints. Creating the part for 3D printing meant that wasn’t an issue.

YD: If you had to list a couple of design references for the Weight, what would they be?

SG: I loved the idea of mixing genres of design using technology as an enabler. I wanted Weight to be minimal and contemporary but fun and whimsical. The base and sphere reflect many different styles and also pay homage to past designs: the Memphis Bay lamp and Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s Bauhaus Lamp to name a couple.

YD: Any designers you particularly look up to?

SG: I got my first taste of lighting design at Paul Cocksedge Studio during my time at university. I helped develop the designs and travelled the world building the installations. The hours were long and intensive, but I’m grateful for the inspiration and experience. Coming from a particularly engineering-based university, it was freeing to be immersed in an environment where nothing had been tried and tested before. We were the first and only team ever to produce the manufacturing methods for Paul’s pieces.

There are other designers that I’ve had the pleasure of working with both in the industry and at university that inspire me greatly. In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever met a creative that doesn’t inspire me in one way or another.

YD: Tell us a little bit about Sam Does Design. Do you ever think about pursuing it full time?

SG: I love that Sam Does Design as a channel is giving back to the community that I’ve learned so much from. I originally started the page to post daily sketches and asked for constructive feedback from the wider design circle. Eventually, I began to notice that people were asking me how I achieved certain things within the world of design, and I began to make the switch to share the knowledge I’d gained. It’s still funny to me that the tiny decision to make an Instagram when I was bored three years ago is having such an effect on my life now. If I thought that it would go anywhere as a career, I would have chosen a better name!

In terms of going full time, I’m so happy at my current day job as a consultant at Precipice. I’ve worked on a variety of amazing projects alongside a multidisciplinary team. Being surrounded by such talented people has helped me grow as a person and designer.

YD: You recently began doing portfolio reviews. Could you give our readers a few quick pointers?

SG: Quick tips: Tell a story. Your portfolio isn’t a siloed list of your skills, it’s an advert for your thought process. Only show your best work. Only show the work relevant to the job you’re applying for. Each portfolio should be tailored to the company. Show work you love doing along with work you want to do more of. Sell your project to me with in-context hero images; I won’t read anything you put in a paragraph.

YD: Any upcoming projects you’d like to talk about? What’s cooking!?

SG: I’m working on some amazing projects at Precipice that I’m unfortunately not allowed to talk about. The Sam Does Design projects coming up include multidisciplinary collaborations across the design world, branching out from industrial and product design. I’m hoping to share a more in-depth process through various collaborations and formats. I’m very excited about how one, in particular, is panning out. Watch this space! “Don’t forget to like, comment, subscribe, hit the bell button and everything else that YouTube asks you to do!”

YD: Lastly, what ever happened to that can of San Pellegrino?! (Sam managed to capture a stray can of San Pellegrino Limon and turn it viral on his Instagram page. I’m surprised the can doesn’t have its own Instagram profile yet.)

SG: The San Pel can that was stuck above the glass elevator for 6 months lives on in our thoughts! A lucky maintenance worker drank it and I caught them on my Instagram Stories. I honestly still think about it every time I have a can, which is more often than I’d like to admit.

Visit Sam Gwilt’s Website or his YouTube Channel for his work/vlogs. Click Here to visit Gantri’s Webstore to buy The Weight.