What if your pasta could lie flat and occupy less shape when packaged, and morph into its desired shape when cooking? As odd as that design brief may sound, scientists at Carnegie Mellon University and Zhejiang University City College are trying to figure out how to make pasta more ‘efficient’. Sure, it may give a couple of traditional Italian cooks and nonnas a panic attack, but hey… science does what science does, right?

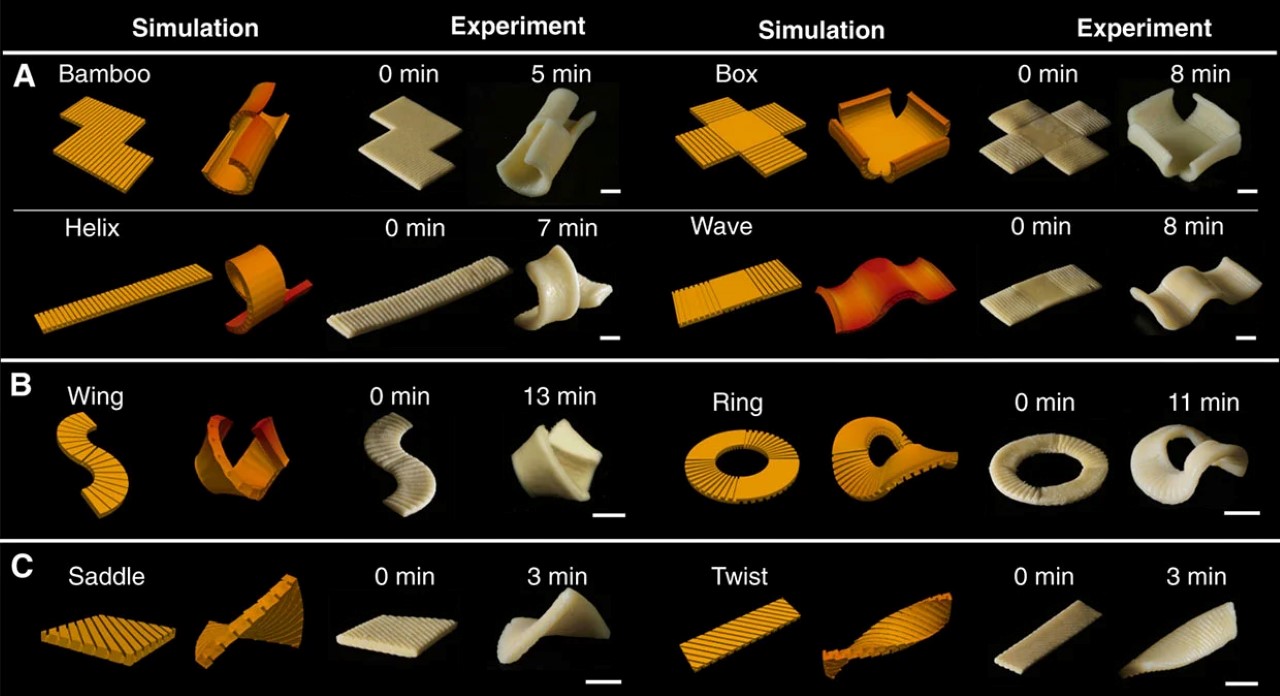

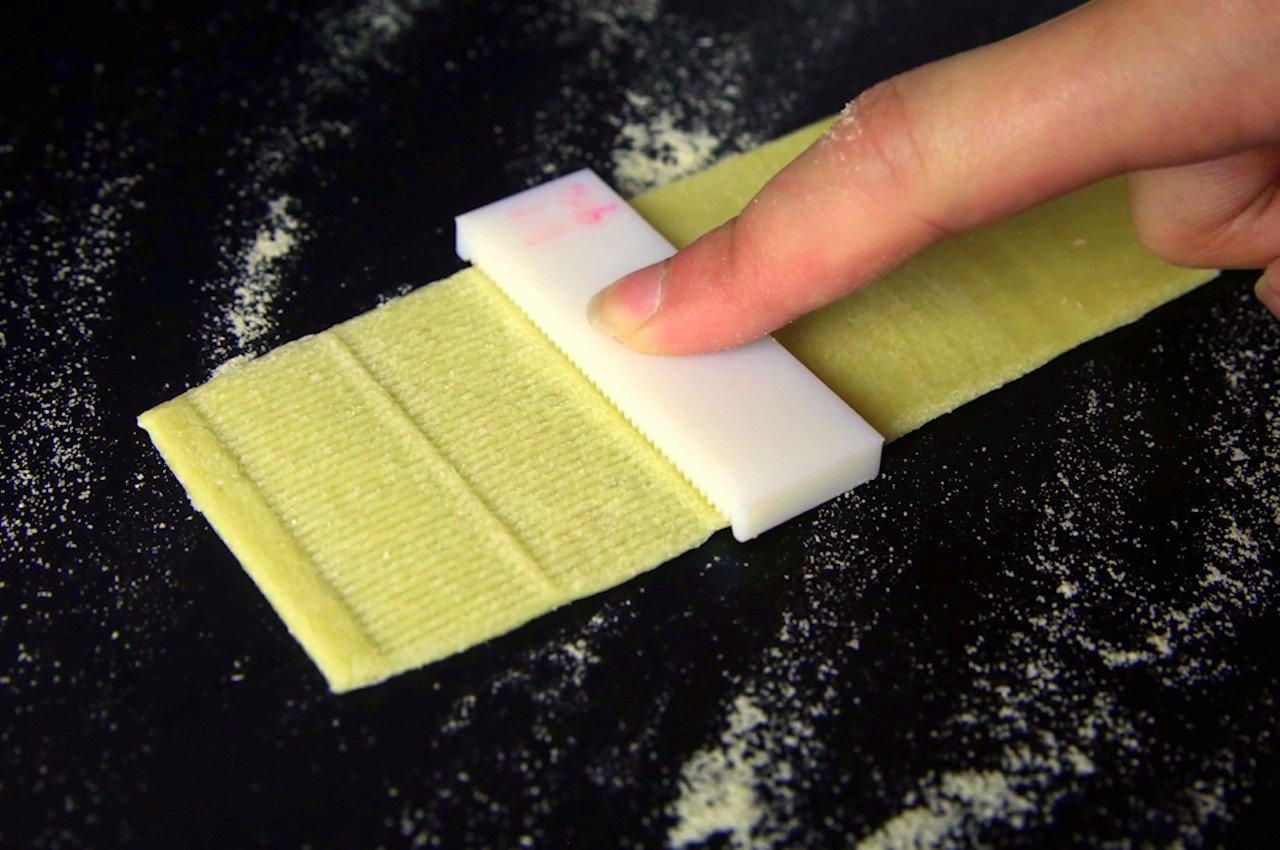

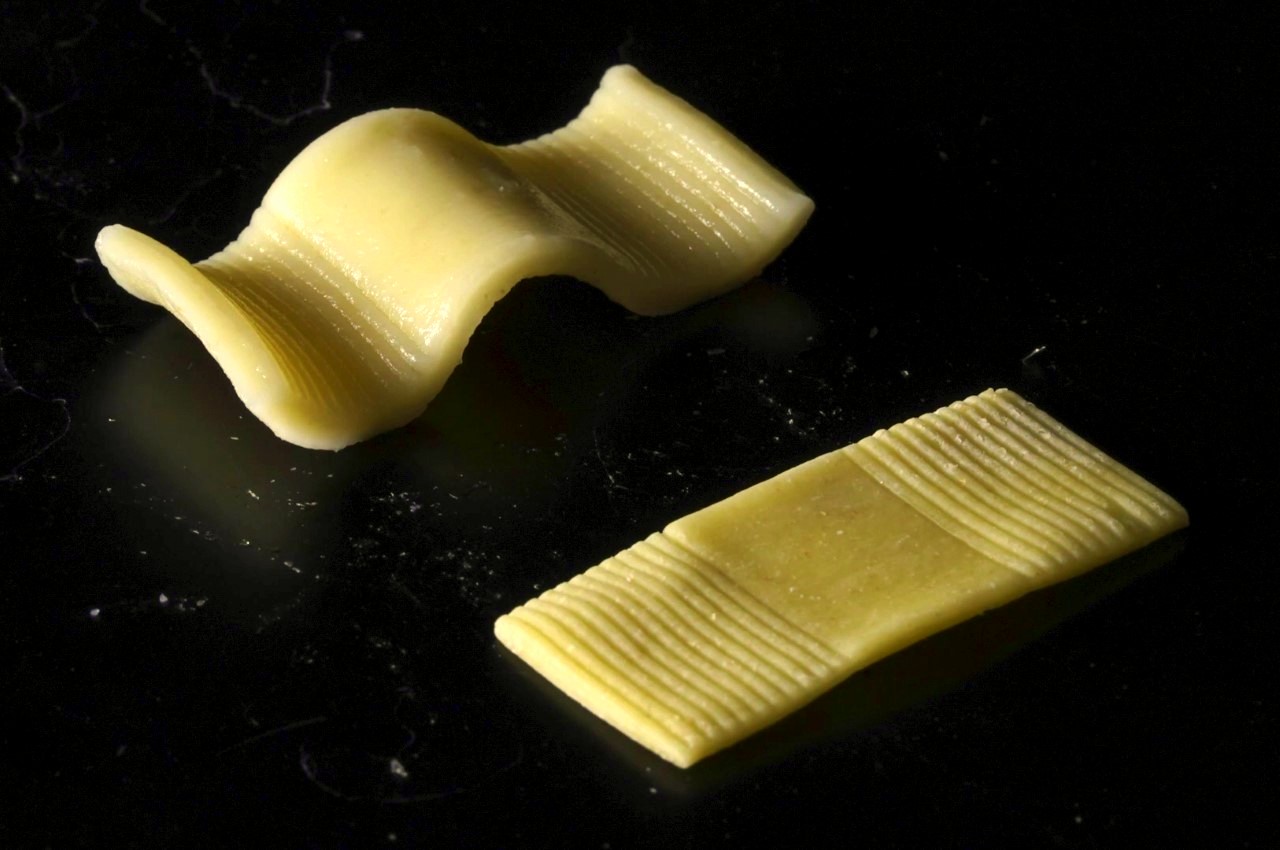

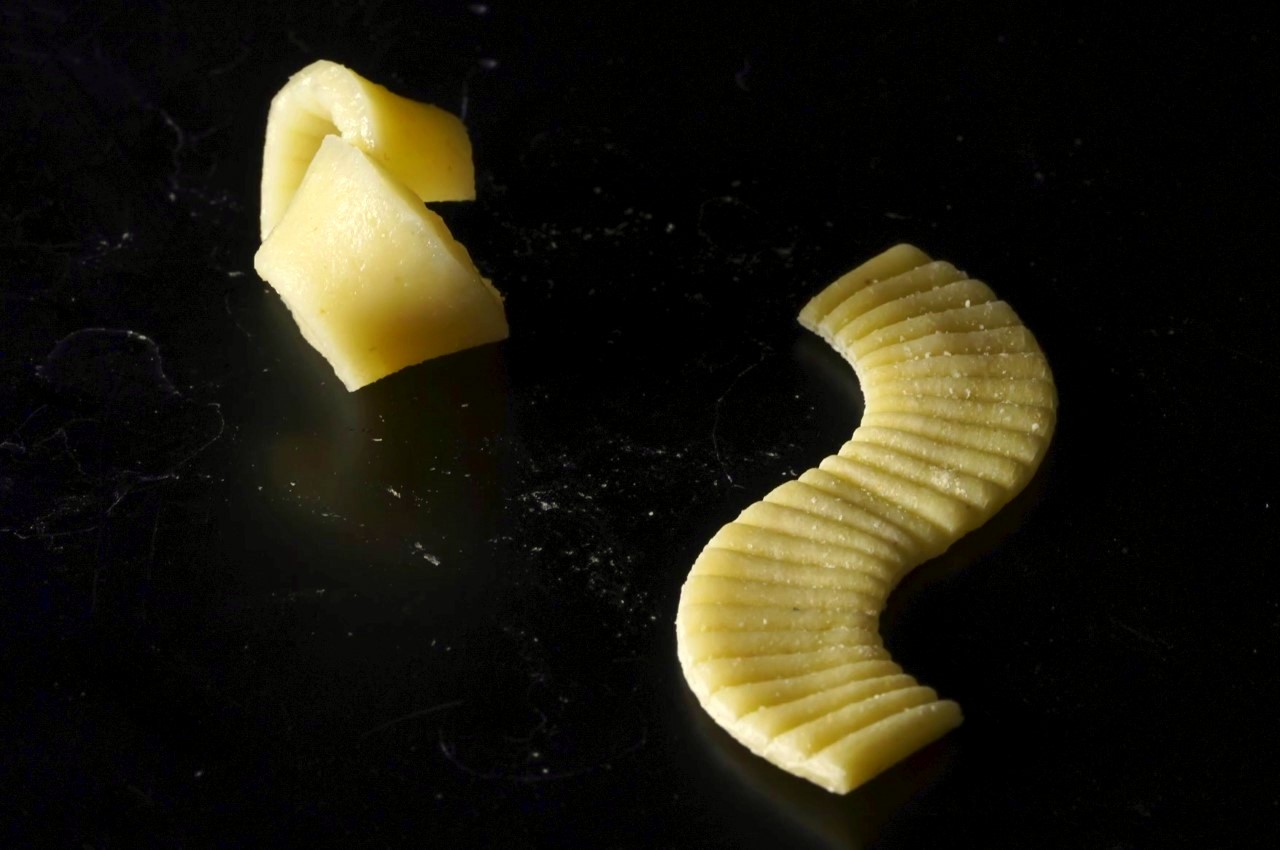

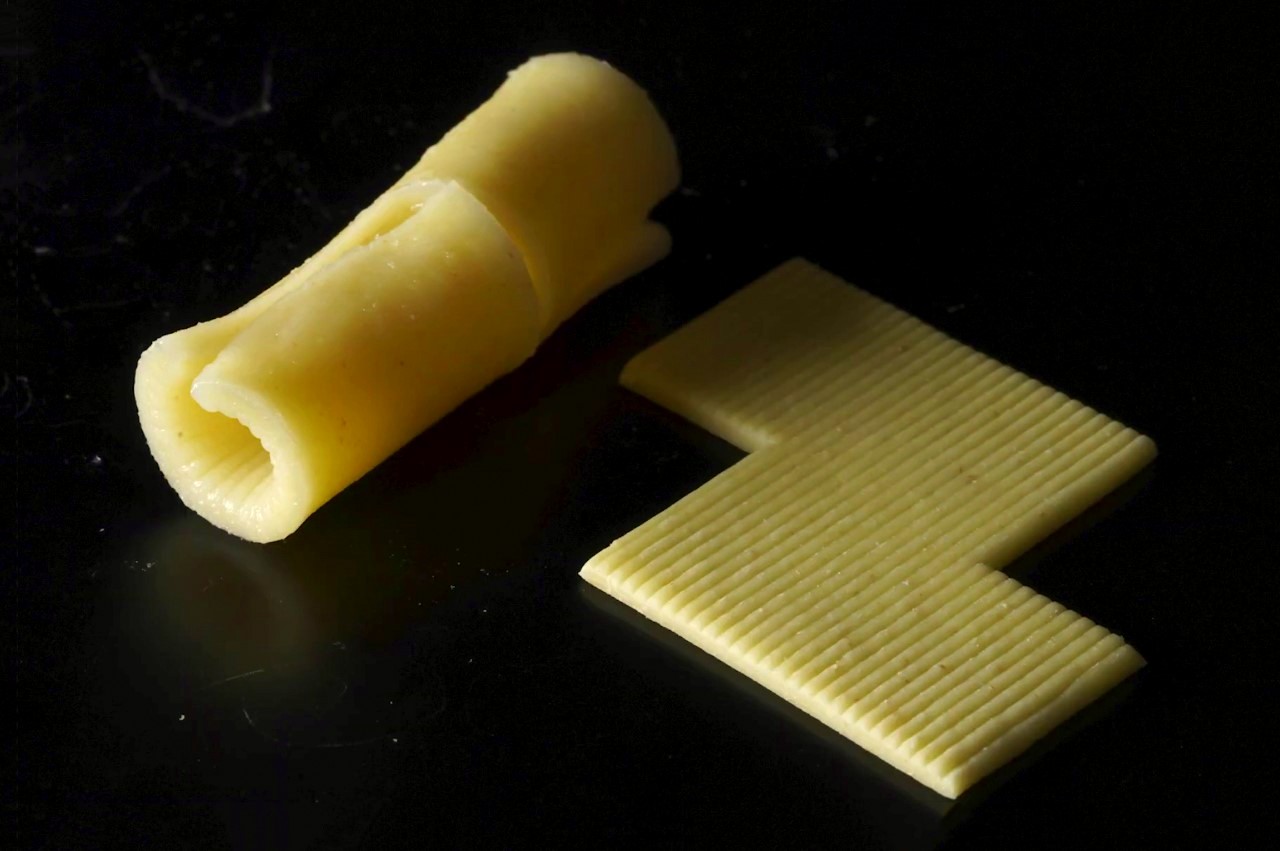

Working on principles that are quite similar to those found in soft robotics and origami, these new pasta shapes start out as flat sheets of dried dough that warp into their signature design when you boil them in water. The secret lies in those unique ridges pressed into the pasta shapes that cause it to warp in different directions when the dough absorbs water and expands. The uniquely calibrated ridge depth and spacing, along with the pasta’s overall shape, result in some wonderfully unusual designs. It’s safe to say that the scientists must have gained a few pounds during the prototyping and testing phases. After all, who wouldn’t want to eat bowl after bowl of pasta for the sake of science??

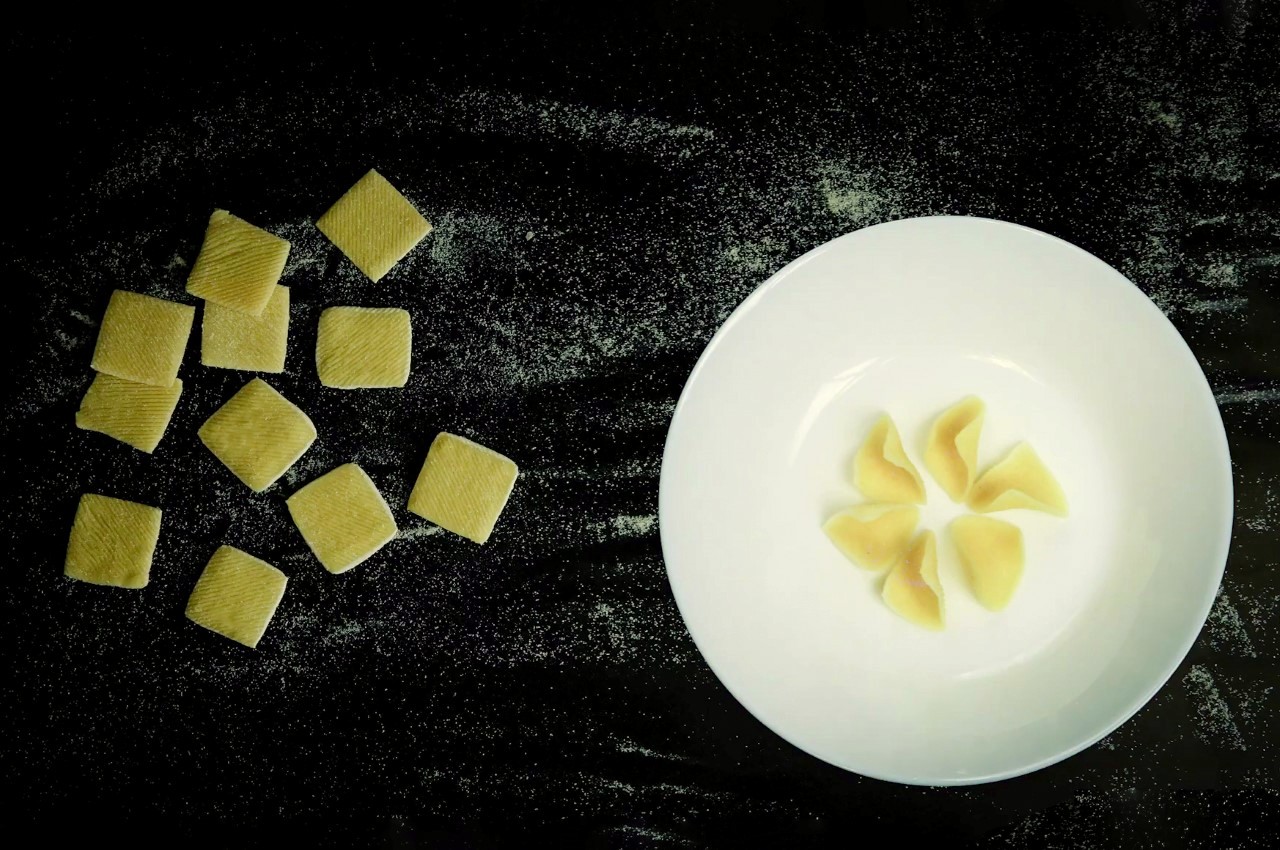

The new pasta shapes are a combination of familiar and absolutely out-of-the-box forms, all calibrated to do two jobs – holding the sauce and tasting fabulous. Some of them are loosely based on popular designs like garganelli, fusilli, and ziti, while other shapes completely redefine the cuisine with how they look… with one clear distinction, creating a pasta that starts off as a flat, scored sheet of dough that transforms into a 3D shape when cooked.

“This mechanism allows us to demonstrate approaches that could improve the efficiency of certain food manufacturing processes and facilitate the sustainable packaging of food, for instance, by creating morphing pasta that can be flat-packed to reduce the air space in the packaging”, say the researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and Zhejiang University.

Designers: Scientists at Carnegie Mellon University and Zhejiang University City College