Generative design has been making waves in aerospace and automotive engineering for years, but it hasn’t really imprinted on consumer tech the way you might expect. Engineers use it constantly to shave grams off aircraft components or optimize chassis structures, then someone wraps the results in conventional styling so customers don’t have to think about the math underneath. The benefits stay hidden, buried under smooth surfaces and familiar forms that don’t challenge our expectations about what products should look like. Consumer electronics especially have remained stubbornly traditional in their design language, even as the tools available to create them have become radically more sophisticated.

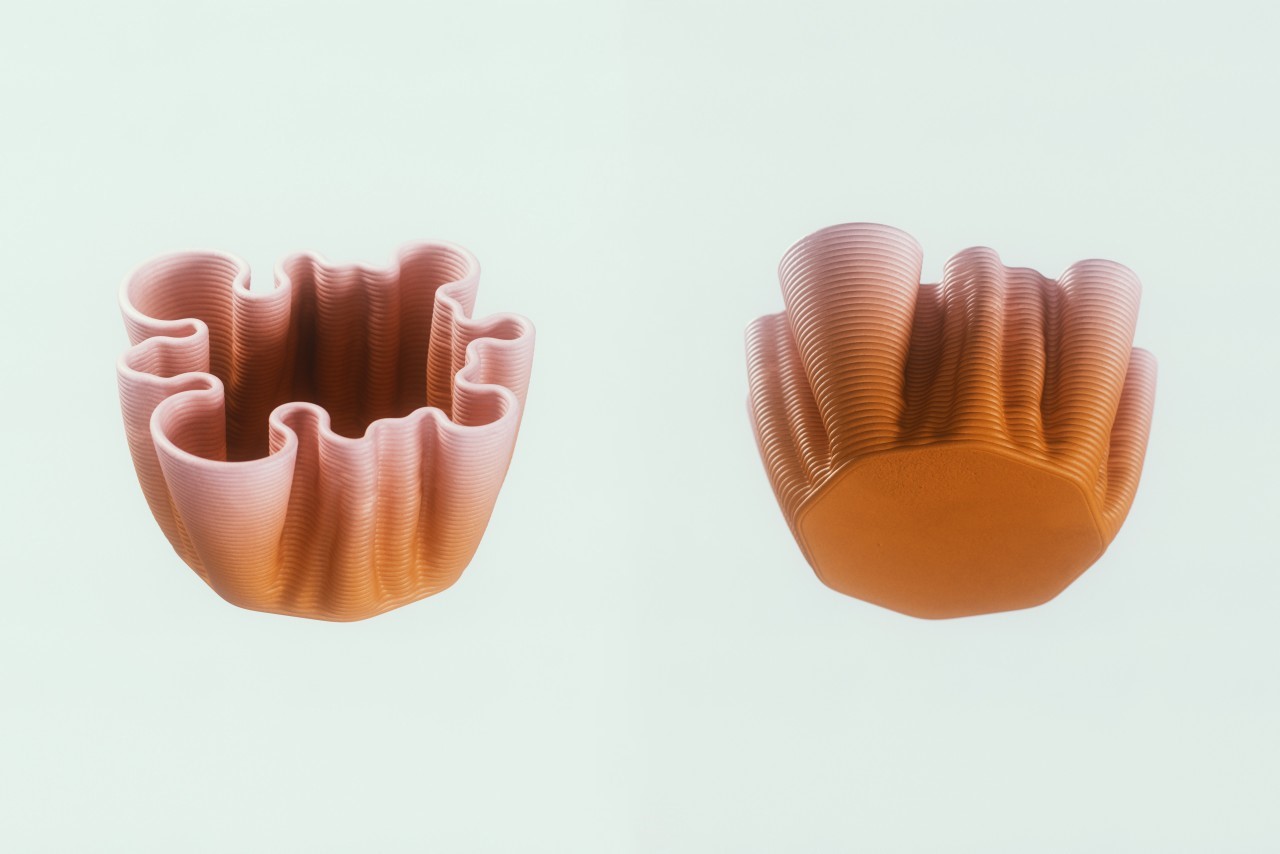

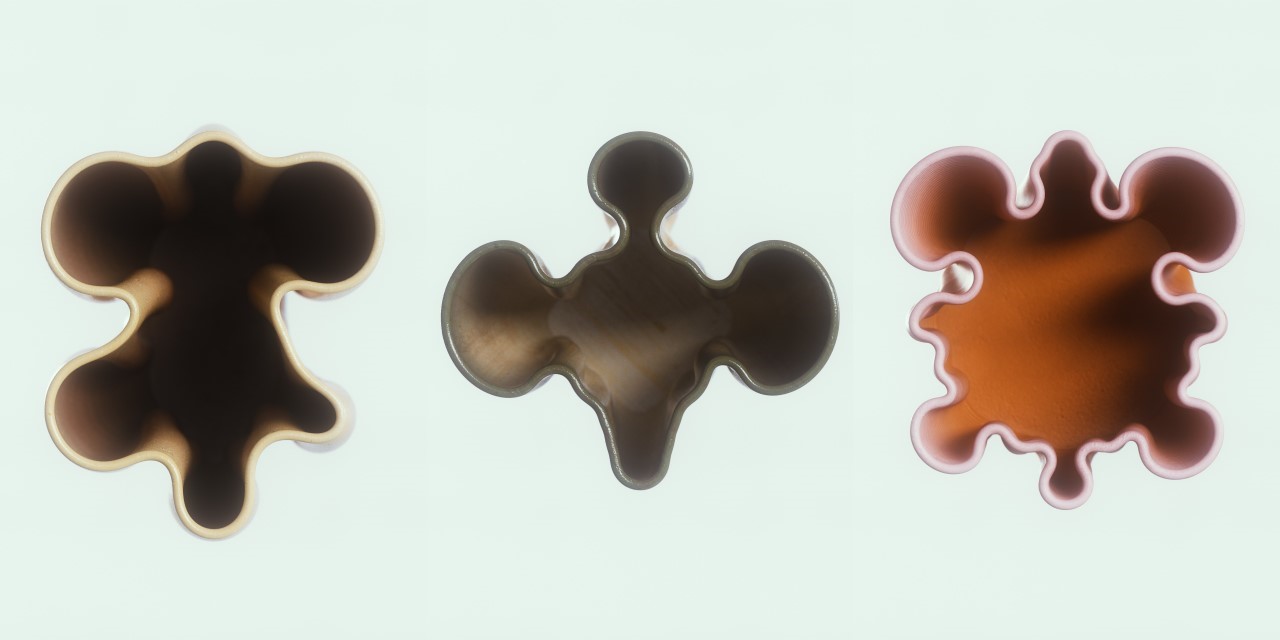

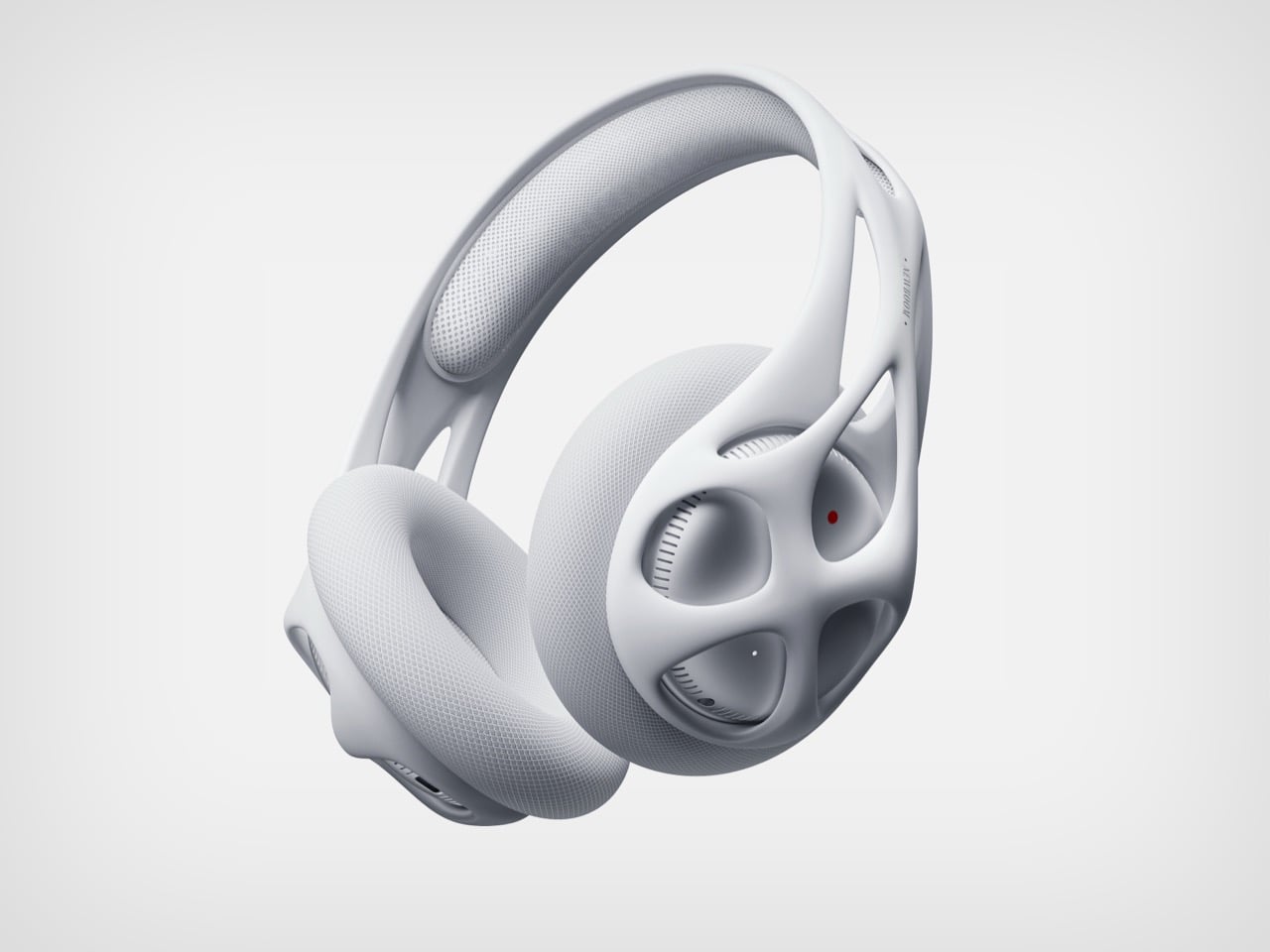

The Grow headset concept takes the opposite approach and puts the algorithm’s output right out front, turning what’s usually a backend engineering tool into the primary design language. What emerged looks less like consumer electronics and more like something that washed up on a beach after spending years underwater. That skeletal structure with its organic voids and flowing curves comes from letting software iterate through thousands of variations, testing each one against structural requirements until it arrived at these forms that feel simultaneously ancient and futuristic.

Designer: Why Design

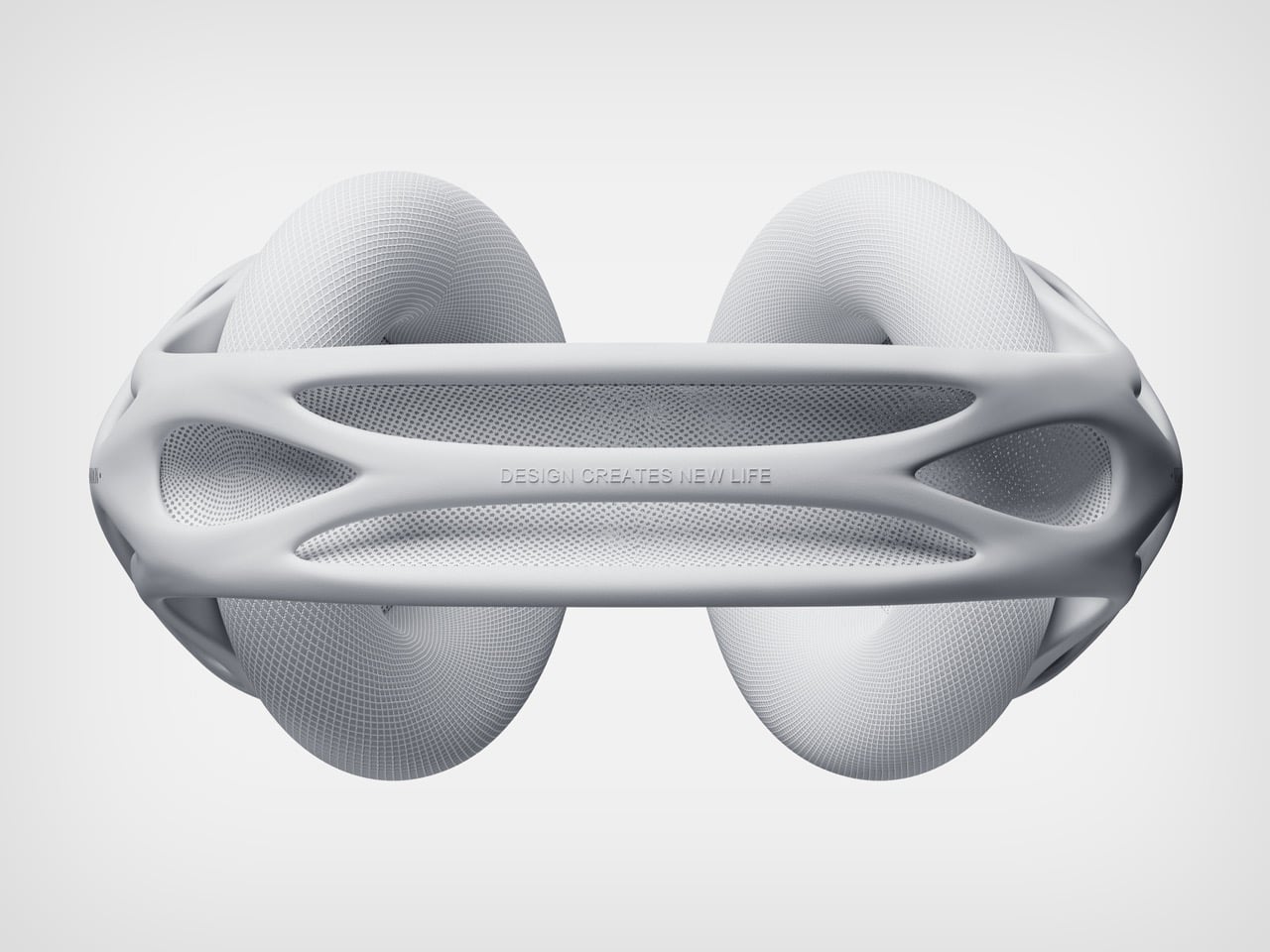

The most striking element is obviously that frame. Instead of the typical headband with internal reinforcement hidden under padding, Grow exposes an exoskeleton of flowing, organic voids that look almost coral-like in their distribution. The algorithm determined where material needed to exist based on stress requirements and where it could be removed to save weight, which is exactly how bone structure develops in nature. Every solid section and every void exists because the math said it should be there.

Look beyond the skeletal outer frame and the Grow headset feels like something you’d find in an Apple showroom. Outer shells made from metal, inner earcups made from a diamond woven mesh. It really feels like Ross Lovegrove or Zaha Hadid were given the reins to redesign the AirPods Max. The design looks bony and alien, but still has a level of pristine-ness to it.

The white and light gray colorway emphasizes that bleached bone aesthetic, though the renders in darker tones show how versatile the form actually is. Change the finish and you get something that reads less natural and more alien, which speaks to how much color influences our perception of organic versus synthetic forms. Either way, you’re getting something that looks fundamentally different from every other headphone on the market.

What Grow proposes is about as radical as the new transparency trend in tech. Sure, transparency is efficient because it just involves a material-switch from opaque to transparent. Grow’s generative design might require way more material than the minimal tech we see around us, but with the right algorithmic tweaking, these next-gen products could actually be tuned to work better, last longer, or be more comfortable. If you ask me, that’s a design trend worth investigating.

The post This Concept Headset Was Grown By Code Instead of Designed By Humans first appeared on Yanko Design.