Most contemporary lamps are adjusted with a dimmer on the cord, a touch sensor on the base, or a slider in an app. That makes light feel like another setting in a menu, slightly detached from the object itself. There is something satisfying about changing light by physically moving parts, as if you are sculpting both the fixture and the atmosphere around it, which is what smart bulbs and app-controlled RGB strips quietly leave out.

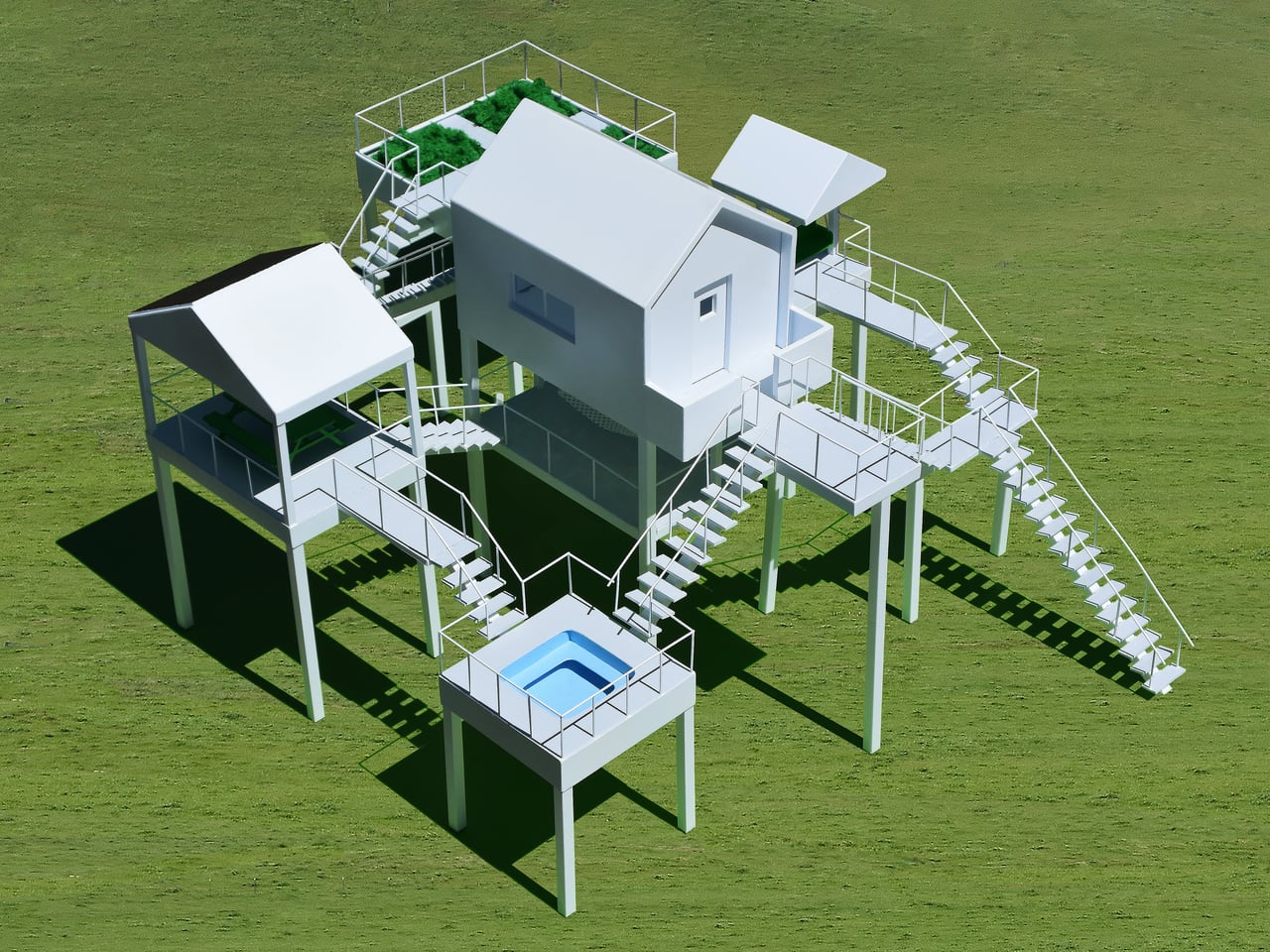

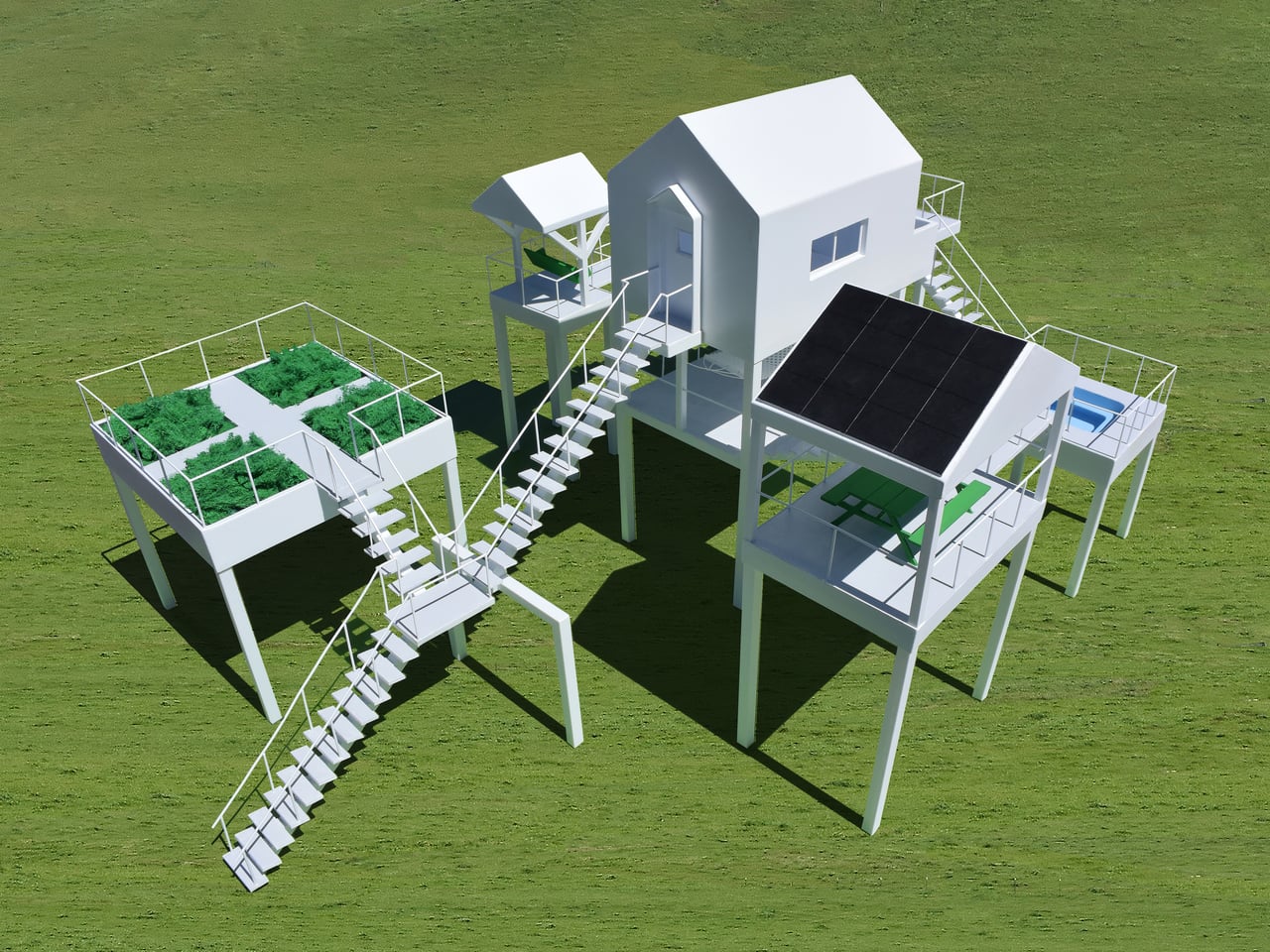

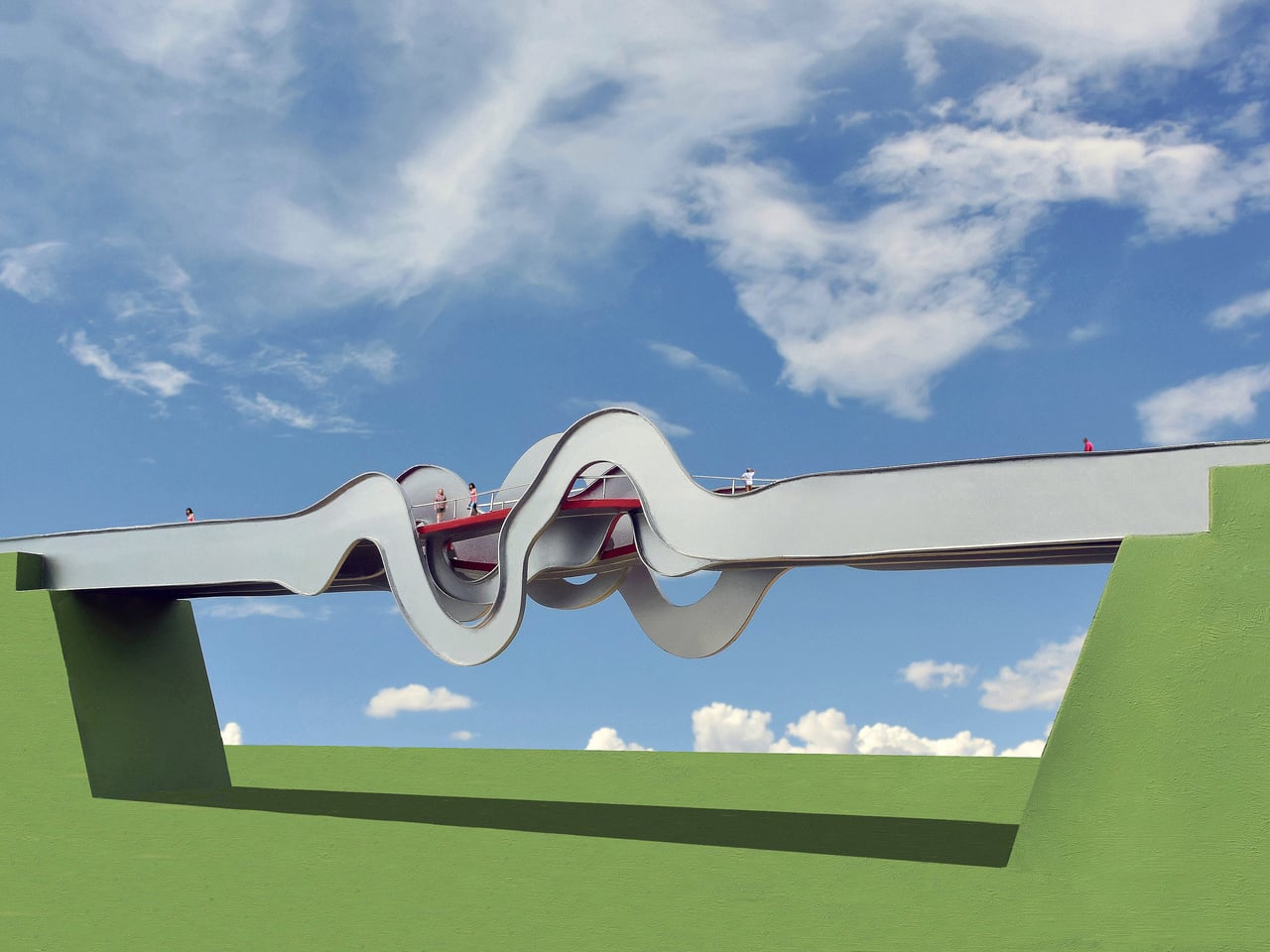

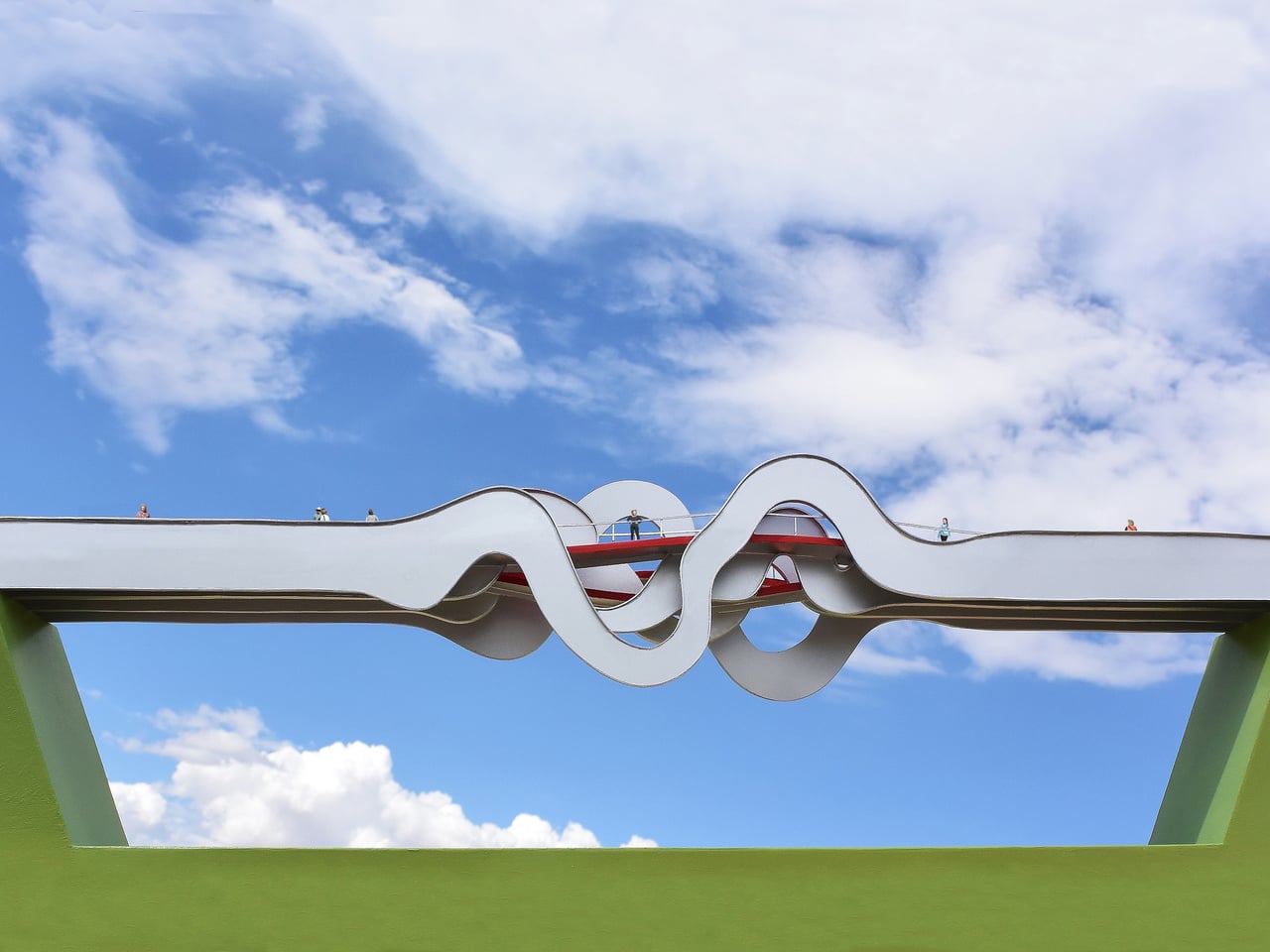

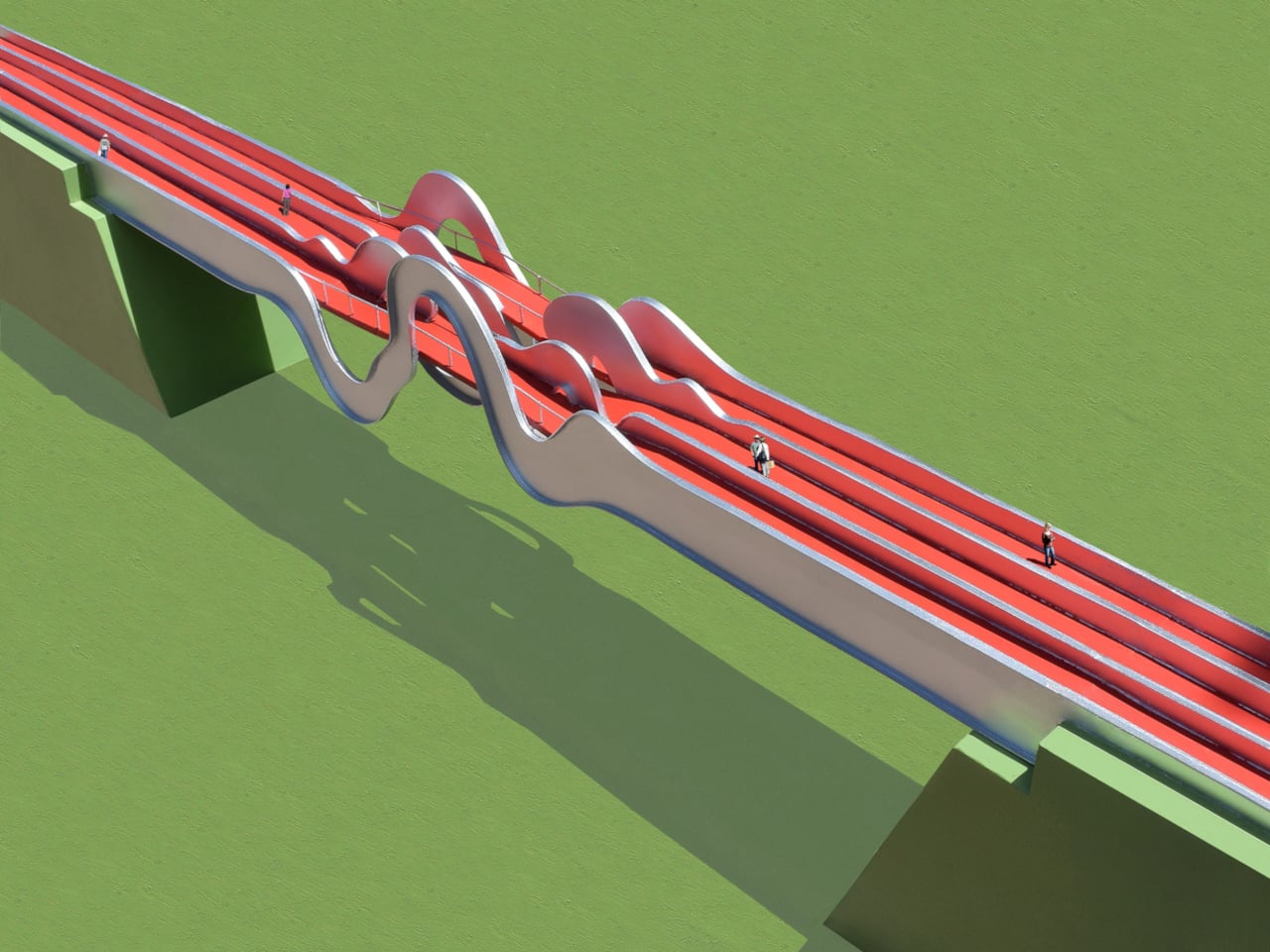

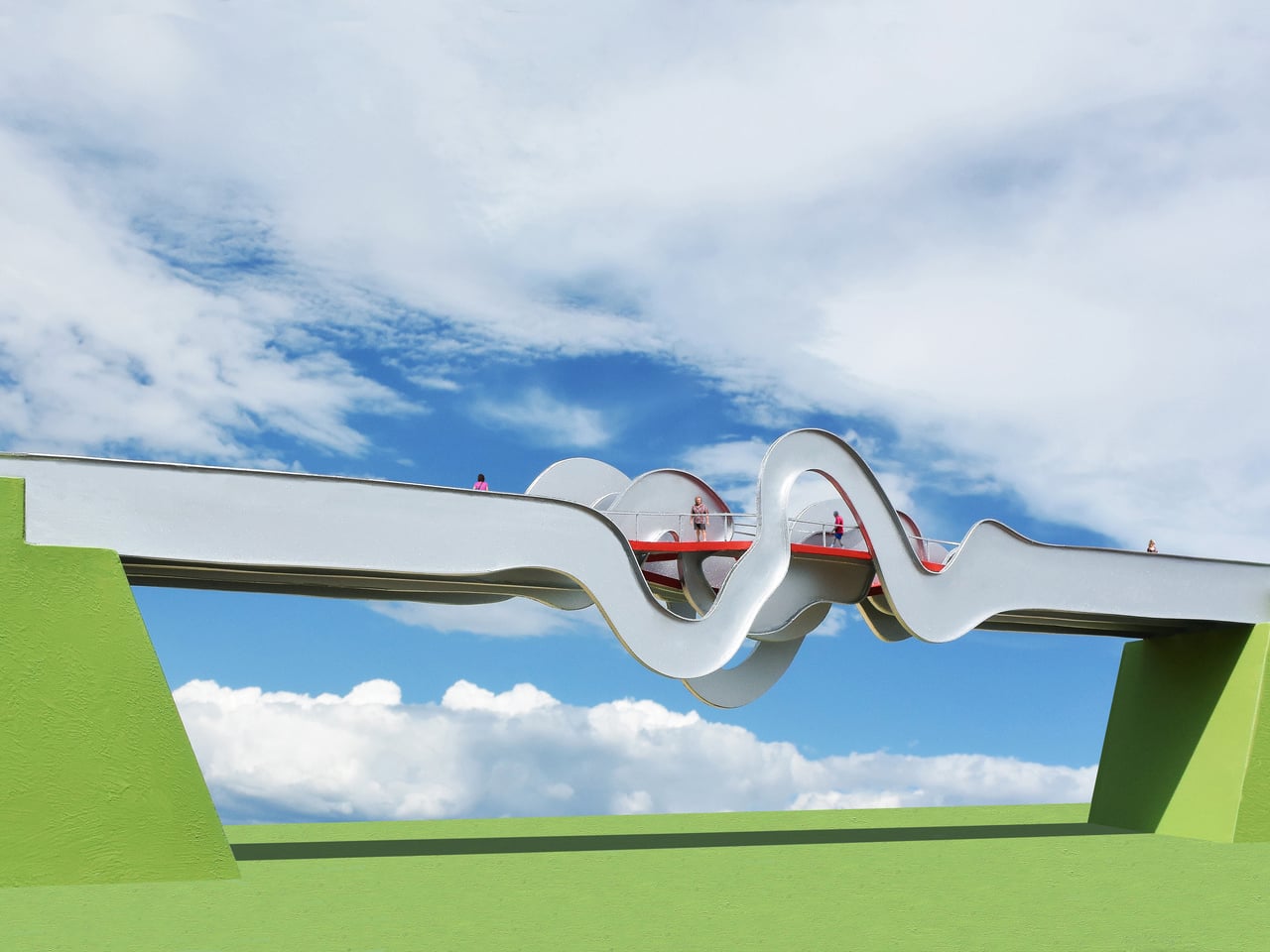

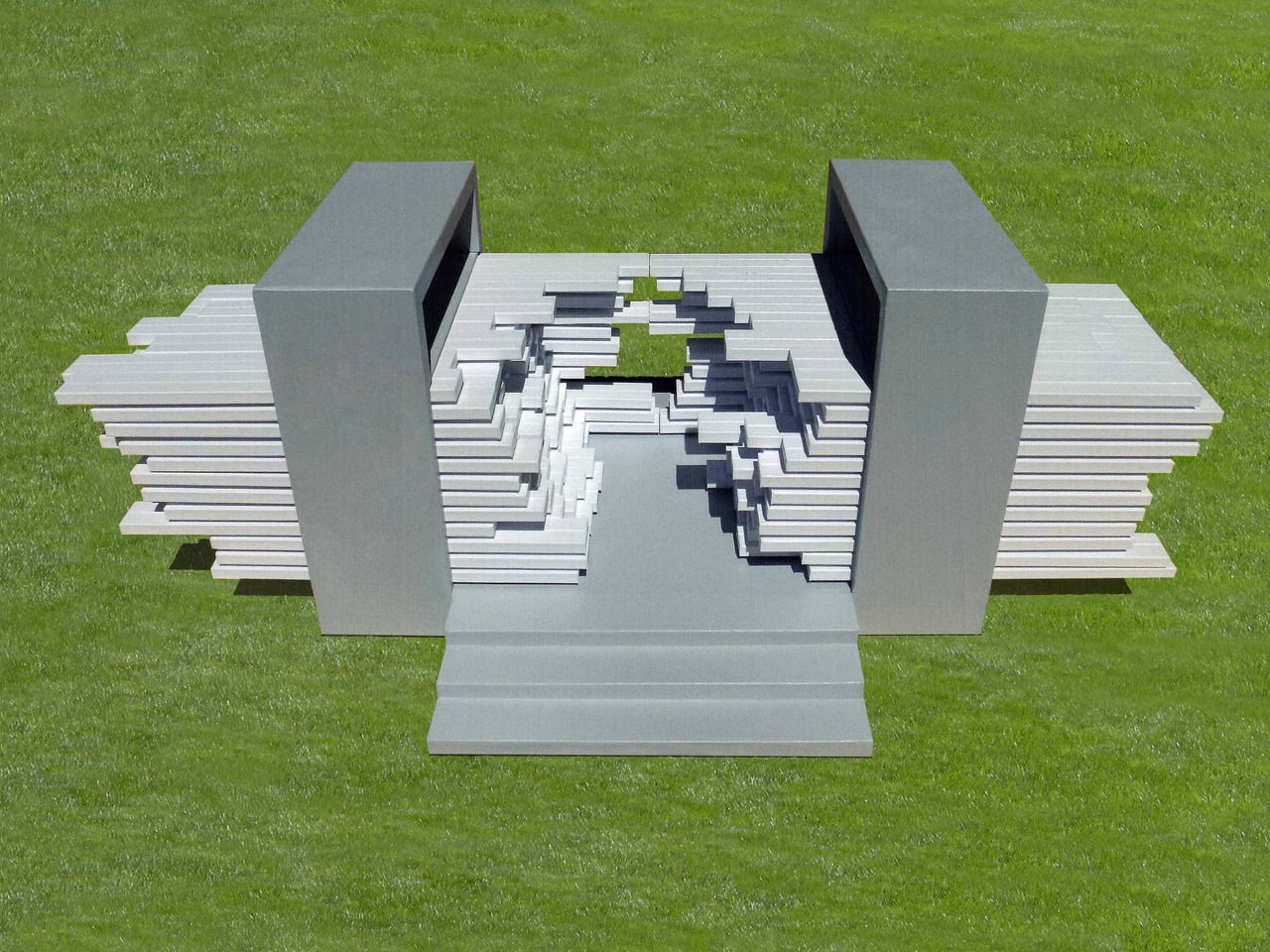

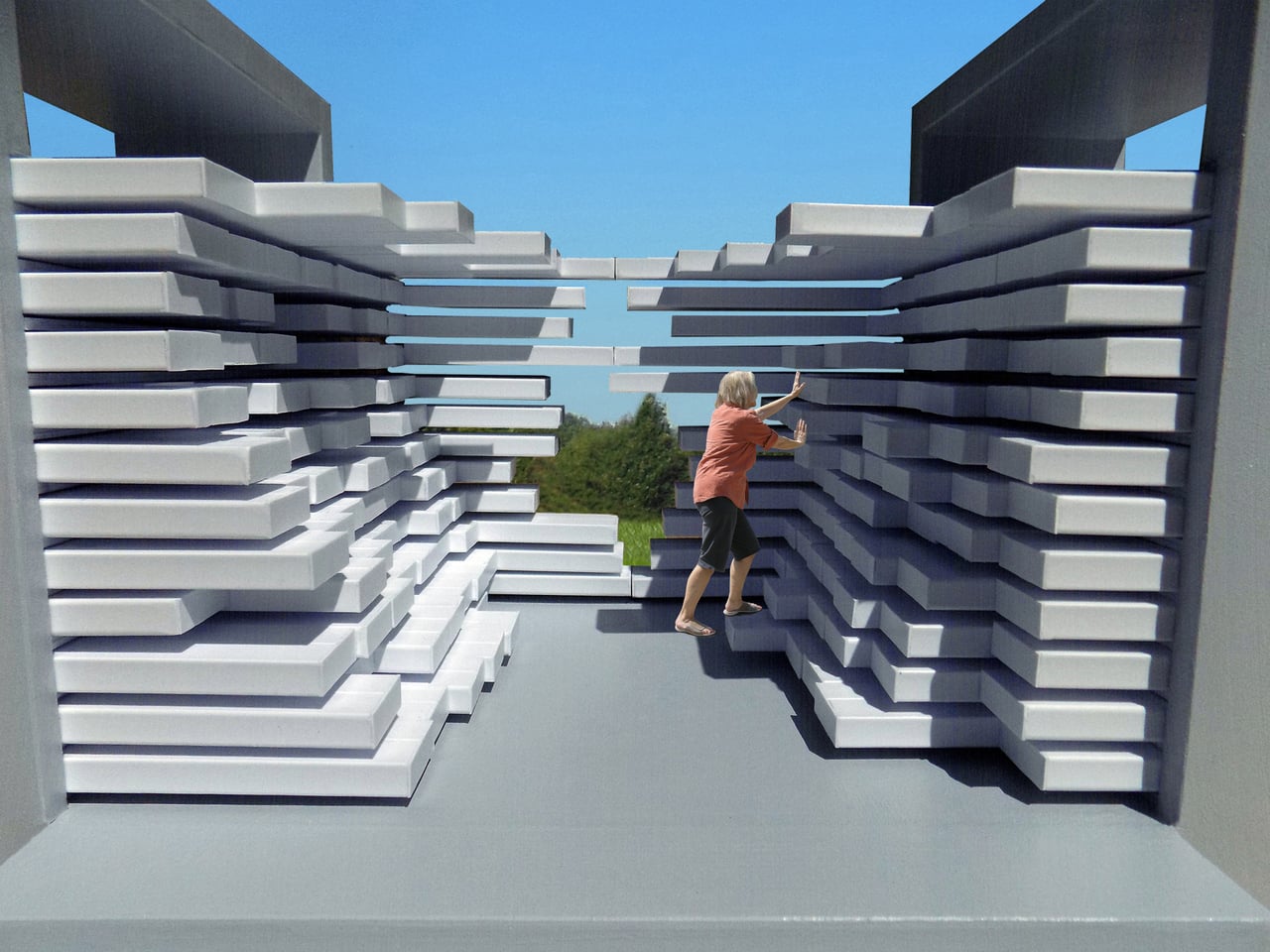

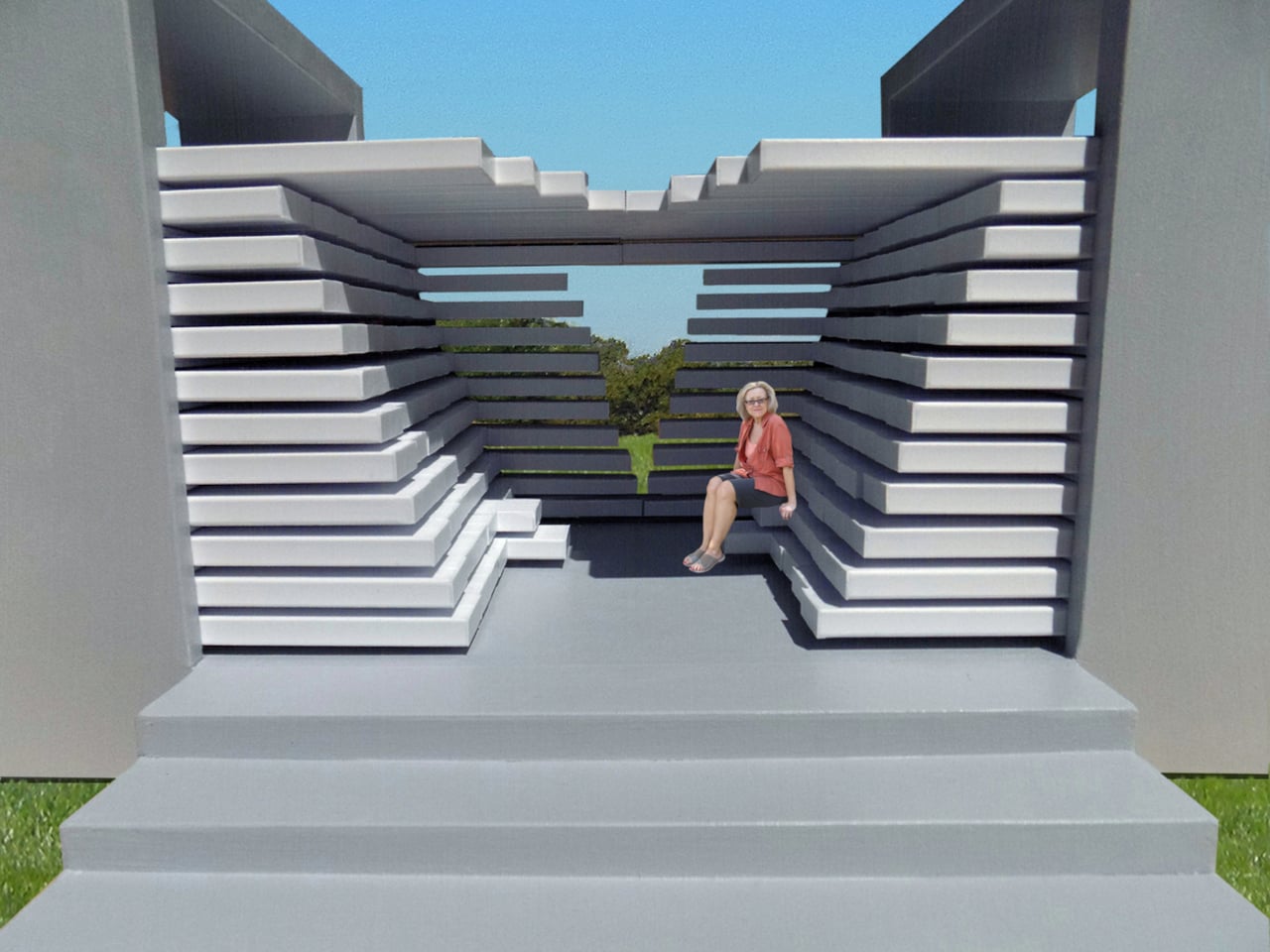

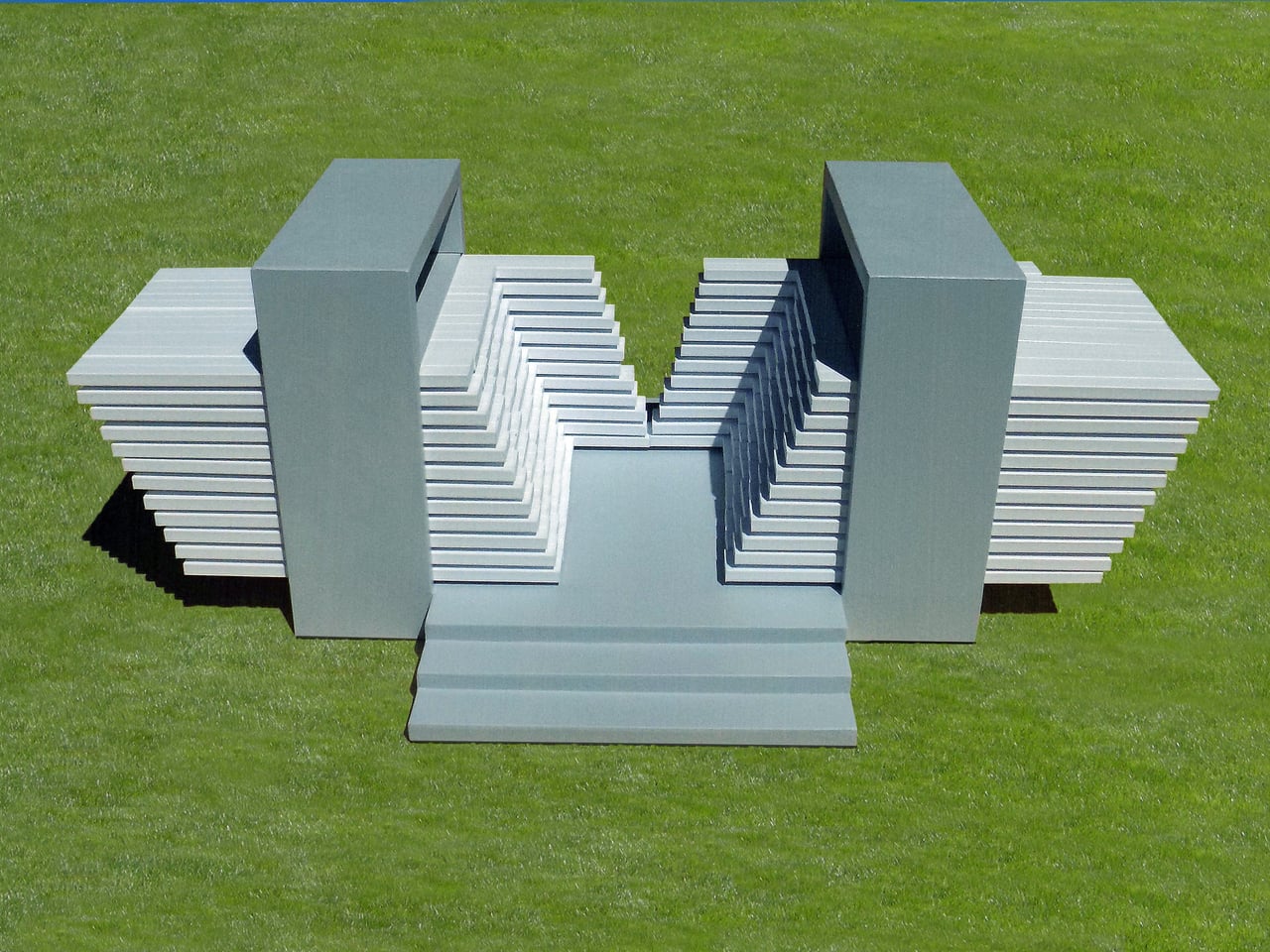

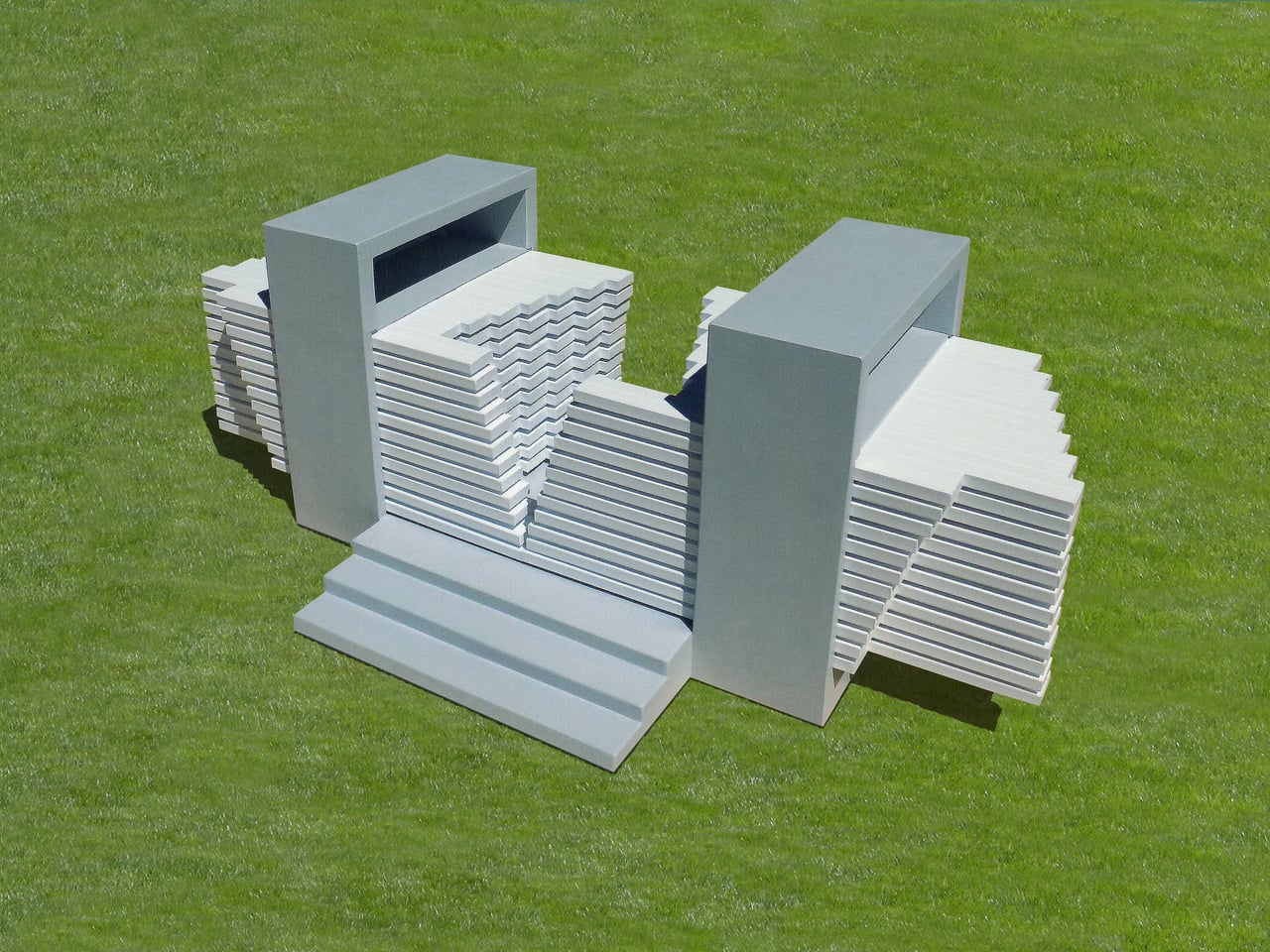

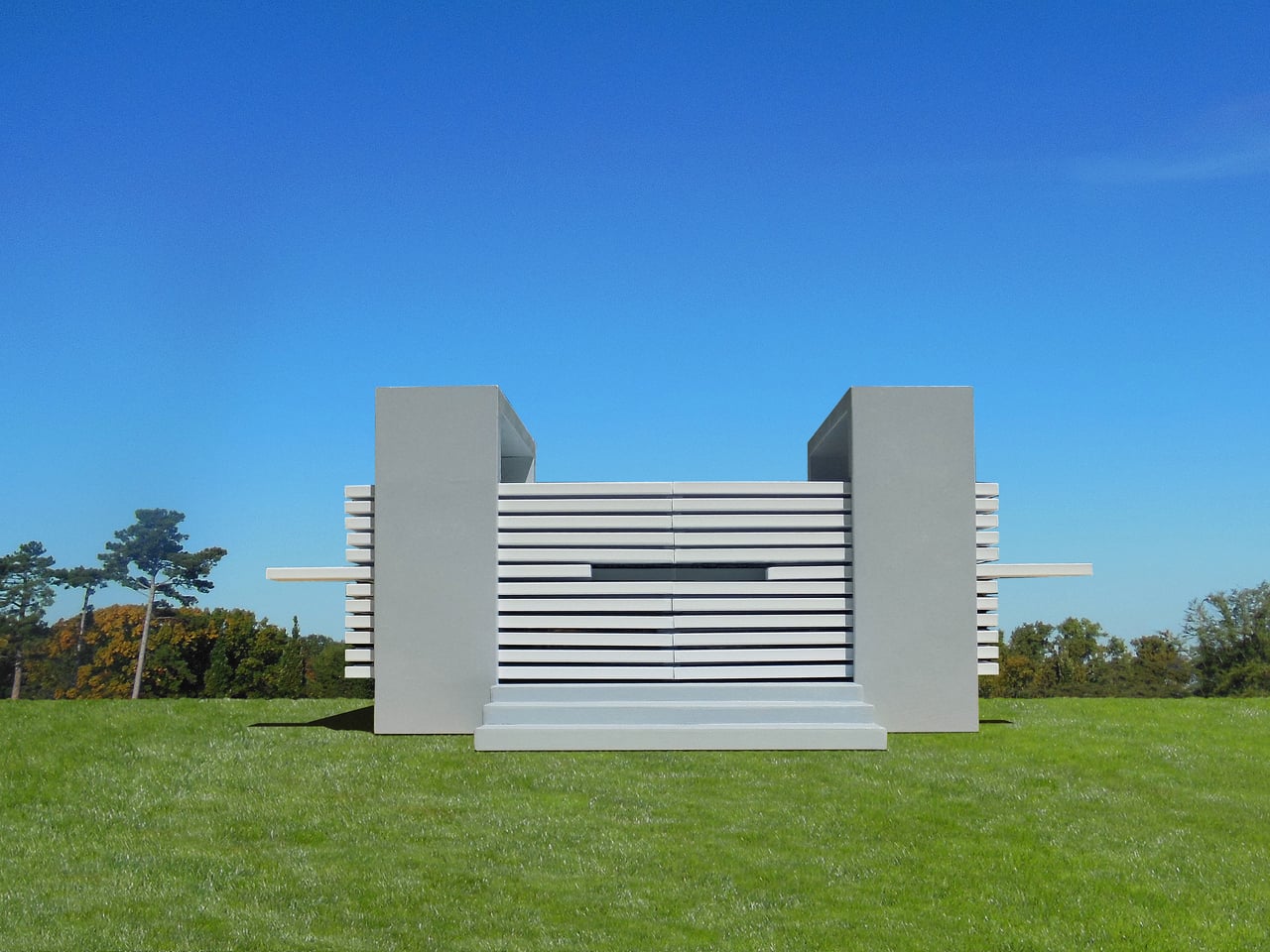

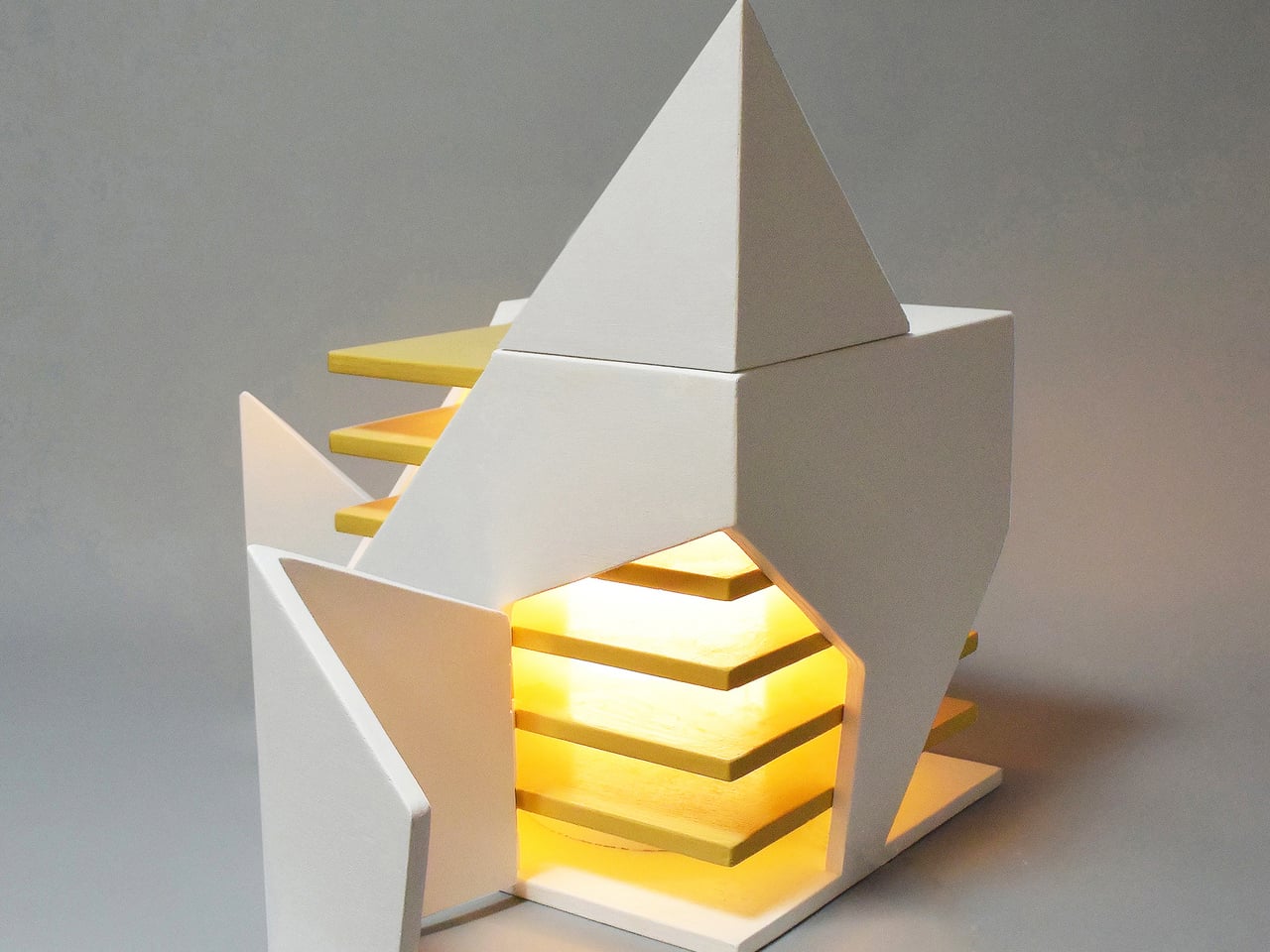

Michael Jantzen’s Interactive Folding Lamp is a small, painted wooden cube that quietly invites that kind of interaction. Four corners of the cube have been cut into different geometric shapes and hinged, so they can swing open and closed. When you start to move them, you aren’t just revealing the light but also changing how much of it escapes. At the same time, you are also changing what the lamp looks like from every side, turning the adjustment into a compositional act.

Designer: Michael Jantzen

A single energy-efficient bulb sits at the center, wrapped in a light-diffusing shield and surrounded by six horizontal yellow planes, evenly spaced like a tiny louvered tower. As you open the hinged corners, more of those yellow planes come into view, catching the light and turning it into a warm, layered glow that spills out through the gaps you have created, contrasting with the cool white painted exterior.

This plays out over a day. The lamp closed down to a near-solid cube with just thin seams of light when you want a soft background presence. One corner folded out to throw a slice of light across a book or keyboard. Multiple panels opened wide when you want the object to become a small, glowing sculpture in the room. Each adjustment is a quick, tactile decision rather than a number on a scale, making the ritual feel manual and deliberate.

Jantzen sees the lamp as part of a larger exploration into re-inventing the built environment through unexpected interactivity. The cube can be read as a piece of micro-architecture, its hinged faces acting like tiny façades or shutters that you reposition to modulate light and form. It compresses the logic of folding pavilions and responsive buildings into something that fits on a side table or desk, letting you interact with architectural ideas at hand scale.

The Interactive Folding Lamp gives you a direct, analog way to tune your space, asking you to touch wood, feel hinges, and watch how light responds. It turns a basic act, turning on a lamp, into a small moment of play and composition. In a time when so much interaction is mediated by screens and voice commands, a lamp that responds only to your hands, opening and closing its own geometry to let light out or hold it in, feels like a quiet reset worth keeping in a corner.

The post Fold the Corners of This Wooden Cube Lamp and Watch the Light Change first appeared on Yanko Design.