Traditional construction is often marked by inefficiencies like material waste, labor intensity, and long project timelines that push up the final cost per square foot. In contrast, 3D printing, or Additive Manufacturing in Construction (AMC), introduces a fundamentally different approach, shifting from subtractive to additive building processes. Its central ambition is to make housing more accessible by lowering material and labor costs while enabling faster delivery of structurally sound, architecturally considered homes.

Yet, despite its transformative potential, 3D printing is not a universal solution. While it offers design flexibility and reduced construction waste, challenges remain around material performance, regulatory frameworks, and the impact on skilled labor. These limitations demand a measured, critical adoption rather than unqualified optimism.

1. Material Integrity and Long-Term Performance

A key challenge in 3D-printed construction is ensuring the reliability and durability of printable materials. Although current cement-based mixes offer rapid curing and high compressive strength, questions remain around their long-term tensile performance, response to diverse climatic conditions, and compatibility with conventional finishes such as plaster layers or vapor barriers. These factors are still under close technical evaluation.

Equally critical is the return on investment measured through longevity. Affordable housing cannot compromise on quality; printed structures must match the lifespan of reinforced concrete buildings. At the same time, reducing environmental impact calls for innovation in geopolymers and locally sourced, recyclable aggregates, redefining sustainable material development.

Two side-by-side concrete homes in Buena Vista, Colorado mark a major construction first for the state. Known as VeroVistas, the houses were built layer by layer using a large-scale 3D concrete printer developed by VeroTouch. One home conceals its printed structure beneath stucco, while the other showcases exposed concrete layers, proving the technology can either blend in or stand out. After extensive research and development, the second home was completed in just 16 days of active printing time using a COBOD BOD2 printer, dramatically reducing labour and construction timelines compared to conventional building methods.

Beyond speed, the homes directly address Colorado’s growing wildfire risk. Built with A1-rated concrete walls, they do not ignite or fuel flames, offering the highest level of fire resistance. Designed to be energy-efficient and mould-resistant, the homes combine durability with everyday liveability. Partnering with local developers and contractors, VeroTouch kept work within the community while introducing innovative construction.

2. Adaptive Spatial Design

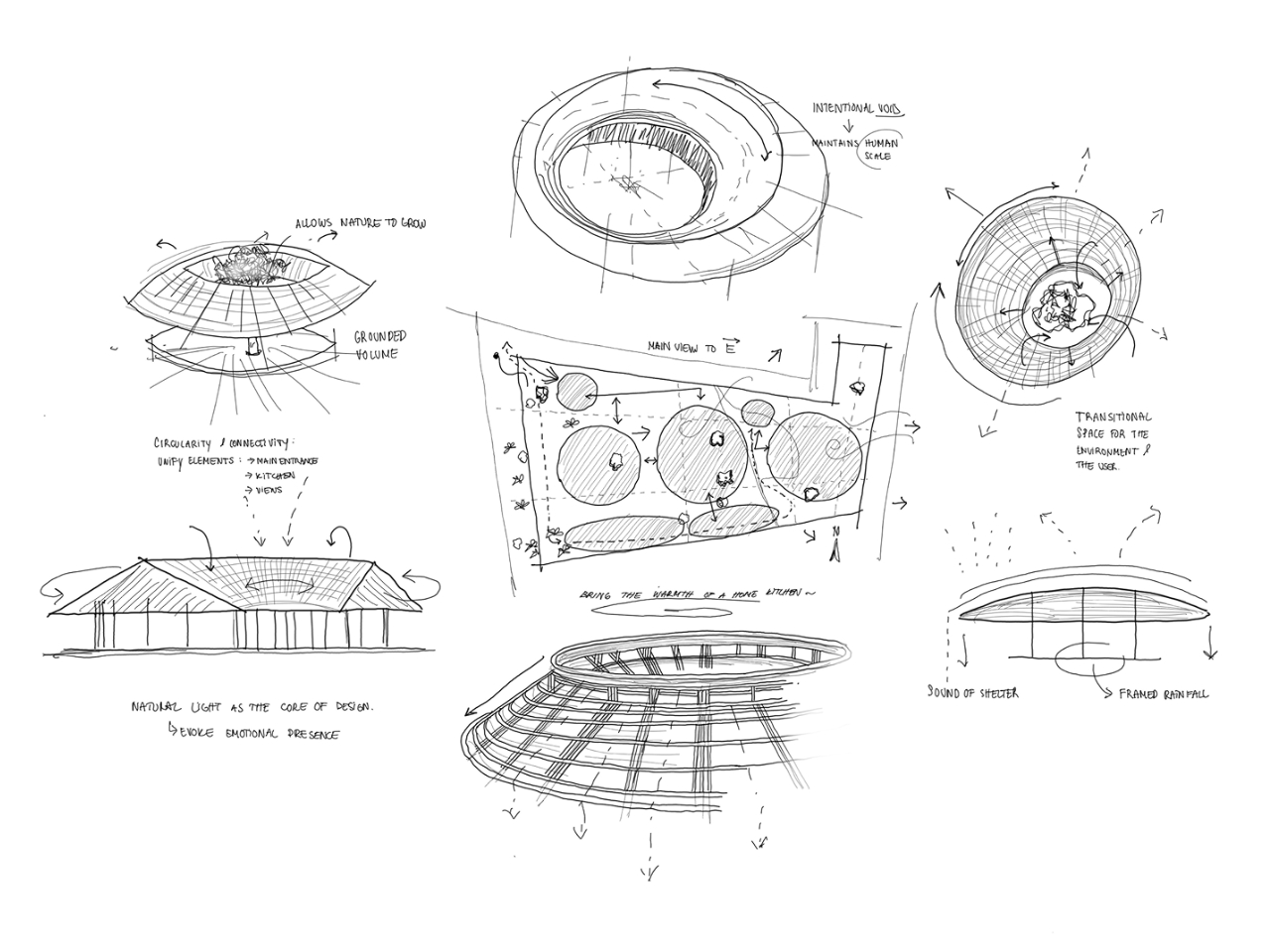

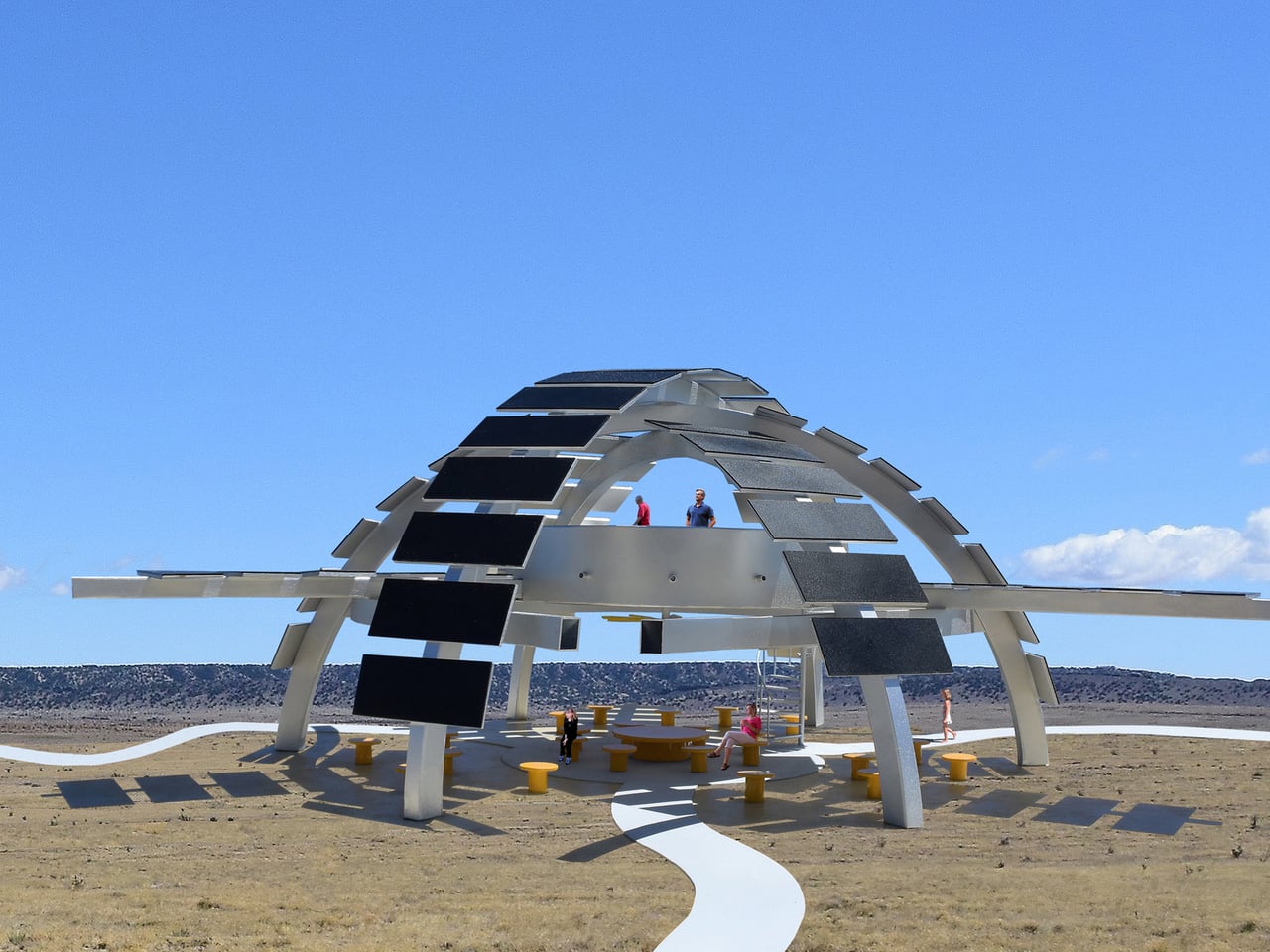

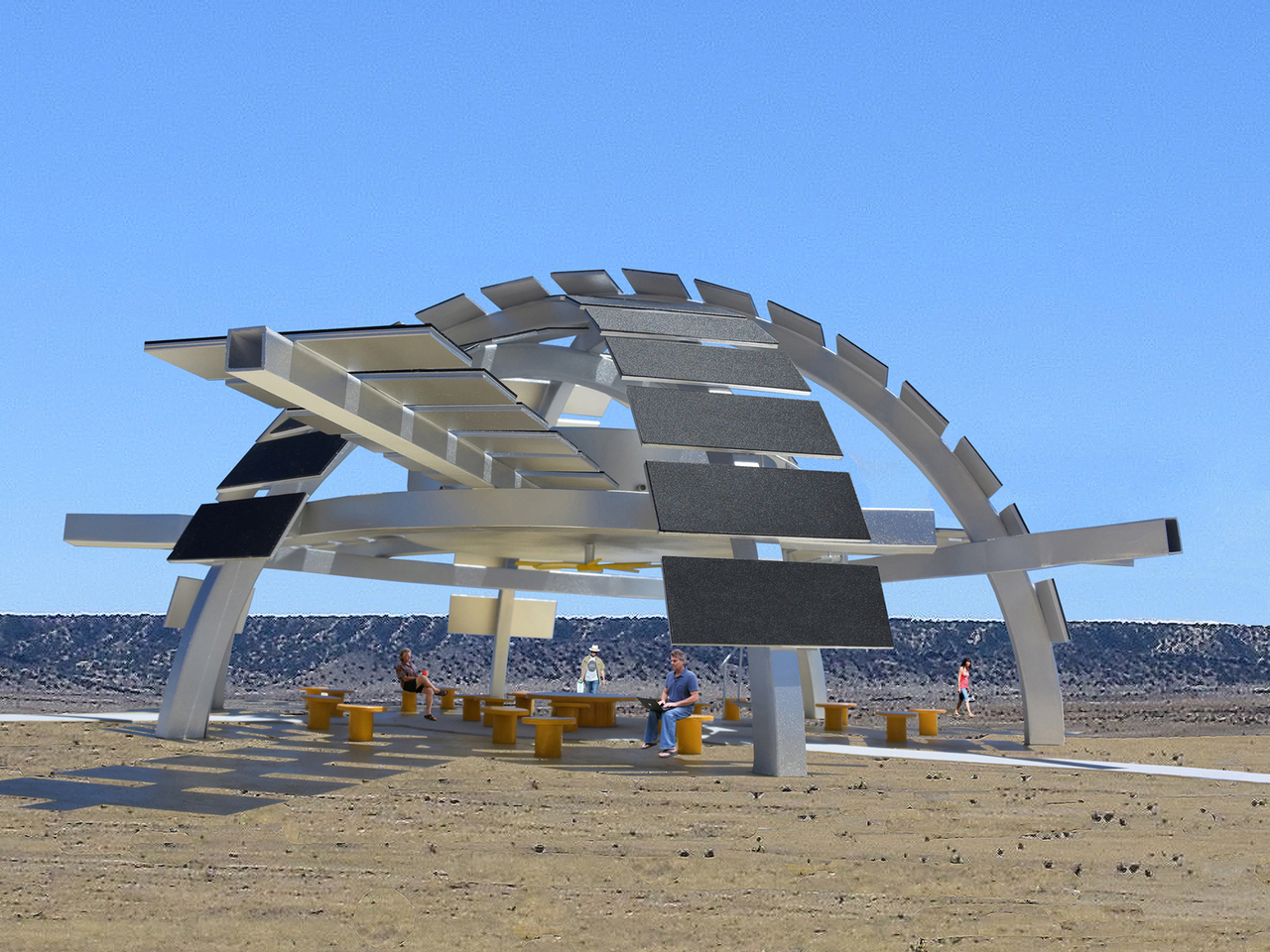

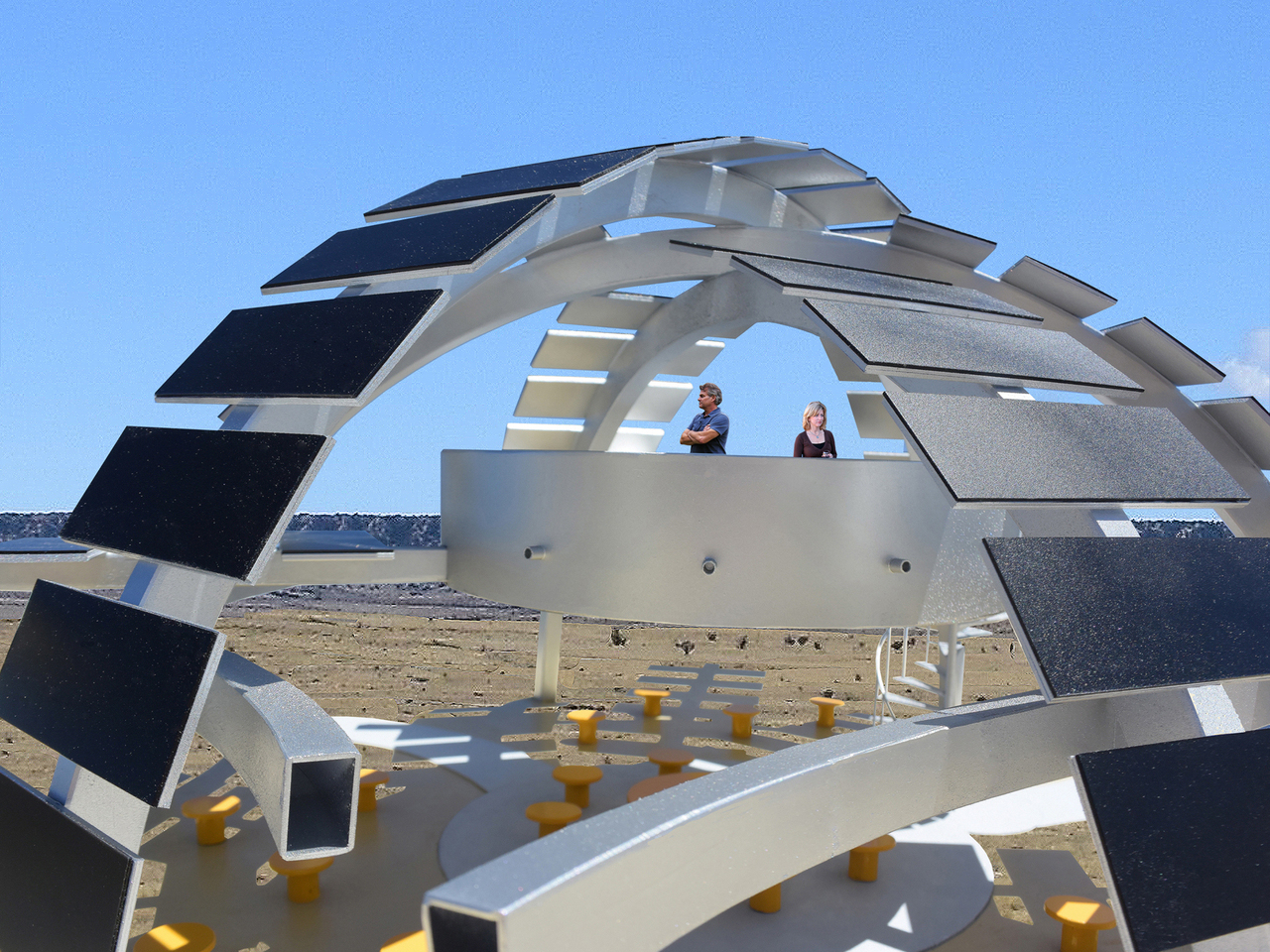

One of the strongest opportunities offered by 3D printing is its ability to enable complex spatial sequencing and customization without escalating costs. Unlike conventional formwork, additive construction allows curvilinear walls, integrated structural elements, and optimized thermal mass to be produced seamlessly, unlocking a level of design freedom once limited to premium architecture.

This shifts housing from basic shelter to architecturally refined living. Digital fabrication helps avoid visual monotony in low-cost homes, allowing floor plans to evolve as experiential journeys. Biophilic strategies and climate-responsive design can be precisely embedded, enhancing comfort while lowering long-term energy consumption.

QR3D, designed by Park + Associates, is Singapore’s first multi-storey 3D-printed home and a bold statement on the future of urban living. Located in Bukit Timah, the four-storey prototype responds to land scarcity with innovation, using digital fabrication to reimagine domestic architecture. Rather than treating technology as spectacle, the house integrates it seamlessly into a familiar residential form, resulting in a structure that is expressive, functional, and suited to dense city life.

The home’s layered concrete façade openly reveals its 3D-printed construction, with most walls fabricated on site by a robotic printer. These textured lines continue indoors, creating visual continuity throughout the interiors. At the centre, a dramatic vertical void connects all four levels, drawing in daylight and enhancing ventilation while adding spatial generosity. Exposed concrete surfaces reduce the need for additional finishes, celebrating material honesty and process.

3. Regulatory Integration Barriers

A major challenge for additive manufacturing in construction is its alignment with existing building codes. Most national and regional regulations are structured around conventional systems such as brickwork, timber framing, and reinforced concrete, leaving limited guidance for layer-by-layer printed structures—especially in areas like fire safety, insulation standards, and service integration.

To move forward, the industry must develop standardized testing and certification frameworks tailored to the tectonic logic of printed buildings. Without regulatory clarity and cross-authority consensus, large-scale adoption remains regionally limited, slowing deployment and restricting the technology’s potential to reduce construction-related carbon emissions at scale.

Tiny House Lux is Luxembourg’s first 3D-printed residential product, designed by ODA Architects as a compact, self-sufficient housing unit for challenging urban plots. Built in Niederanven using on-site 3D concrete printing and locally sourced aggregates, the home demonstrates how advanced construction technology can unlock the potential of narrow, previously unusable land. Measuring just 3.5 metres wide and 17.72 metres deep, the 47-square-metre structure is engineered for efficiency, with printed concrete walls completed in about a week and the full build finalised within four weeks. Its ribbed concrete surface functions as both structure and finish, creating a durable, low-maintenance exterior that responds to daylight.

Inside, the house prioritises clarity and performance. A linear layout runs from the south-facing entrance to the rear, maximising natural light and ventilation, while services are neatly integrated along the sides. Underfloor heating powered by rooftop solar panels ensures energy autonomy and reduced operating costs. As a replicable housing solution, Tiny House Lux positions 3D printing as a viable, scalable product for municipalities seeking efficient, affordable residential options.

4. Low-Carbon Construction Speed

The most transformative opportunity of 3D printing lies in its ability to dramatically accelerate construction while reducing site waste. Core structural shells can be printed within days, shortening project timelines and lowering labor demands. This speed directly supports carbon reduction by optimizing material use and cutting down on transport and logistical emissions.

Here, the technology delivers its strongest return on investment. On-demand printing minimizes waste and compresses on-site activity, reducing environmental and neighborhood impact. These efficiencies position 3D printing as a powerful solution for rapid disaster response and scalable affordable housing development.

Portugal-based firm Havelar has constructed its first 3D-printed home, produced in just 18 hours using a COBOD BOD2 printer. Located in the Greater Porto area, the single-storey residence is designed as a compact two-bedroom dwelling. A robotic printer extrudes a cement-based mixture layer by layer to form the structure, significantly reducing build time and reliance on intensive labour.

Once printing was complete, traditional construction methods were used to install the roof, windows, doors, and interior fittings, bringing the total construction timeline to under two months. The home features ribbed concrete walls that clearly express its printed origin, along with a simple, efficient layout comprising a central kitchen and dining area, living space, bathroom, and two bedrooms. While minimal in finish, the project prioritises accessibility and efficiency. Havelar sees this prototype as a foundation for scaling production and transitioning to alternative materials, with long-term ambitions of achieving carbon-neutral construction.

5. Scalability and Logistics Constraints

A major challenge in construction-scale 3D printing lies in the size and mobility of printing systems. Large gantry frames and robotic arms are costly to transport and complex to assemble, often offsetting the time saved during the printing process itself. In addition, reliable access to uniform printing materials remains limited, particularly in remote or developing regions where affordable housing demand is highest.

True scalability requires a shift toward compact, modular, and easily deployable machines. Cost evaluations must factor in equipment mobilization alongside material and print efficiency. Until printing systems become as flexible as the designs they produce, widespread economic viability remains constrained.

Designed by BM Partners and produced using a COBOD BOD2 printer, this unnamed home in Almaty, Kazakhstan, is recognised as Central Asia’s first 3D-printed residence. The project demonstrates how additive construction can meet demanding environmental and seismic conditions. Built with resilience in mind, the house is engineered to withstand extreme temperatures and earthquakes of up to magnitude 7.0. Its walls can be printed in just five days, significantly reducing construction time while offering a more economical alternative to conventional housing methods.

A high-strength concrete mix with a compressive strength of nearly 60 MPa was used, far exceeding typical local materials. Made from locally sourced cement, sand, and gravel and enhanced with a specialised admixture, the mix was tailored to regional conditions. Expanded polystyrene concrete offers thermal and acoustic insulation, providing comfort across a wide range of temperature variations. Once printing was complete, conventional construction teams added windows, doors, and interiors.

3D printing in construction marks a critical intersection of innovation and social responsibility. Despite challenges in materials and regulation, its advantages in design flexibility and rapid delivery make it inevitable. Treated as a new tectonic system and not merely a tool, it can redefine affordable housing by uniting efficiency, quality, and architectural value.

The post 5 Countries Just 3D-Printed Homes in Under a Week: The Future Is Here first appeared on Yanko Design.