Our homes and appliances are becoming more powerful, but they are also becoming more complicated. Many interfaces are fortunately being reworked to simplify our interaction with these devices, but almost all of them still require a clear view of what the interfaces are. Sure, there are voice commands nowadays, as well as AI, but as any smart homeowner has experienced, these aren’t always fast or reliable. Unfortunately, all these new interfaces, even the minimalist ones, tend to cut off those with vision disabilities, depriving them not only of enjoyment or convenience but also of a sense of confidence and security in their own homes. It doesn’t actually take much to design with accessibility in mind, and as these three smart device concepts show, such creative designs might be useful or even fun for those who can see perfectly as well.

Designer: Jaehee Lee, Byeonguk Ahn, Minseok Kim

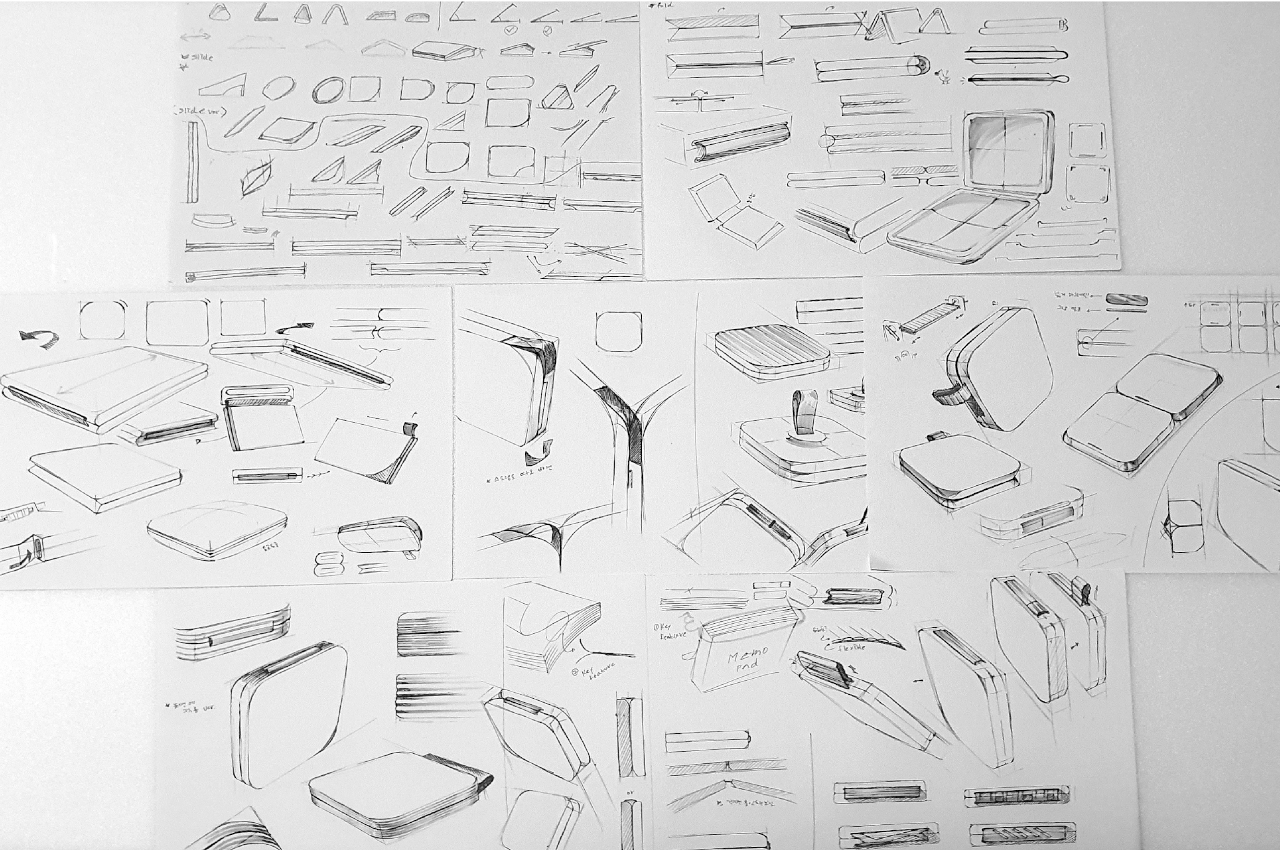

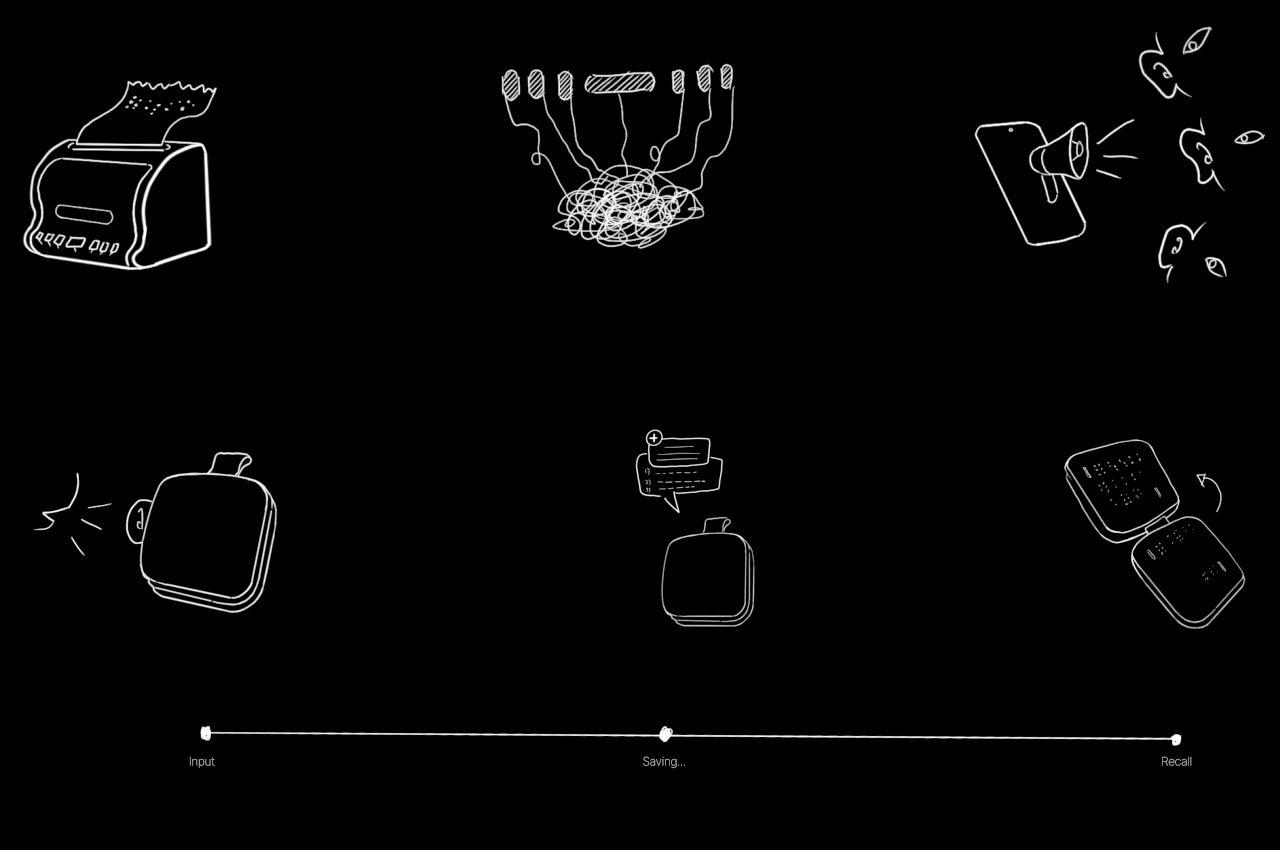

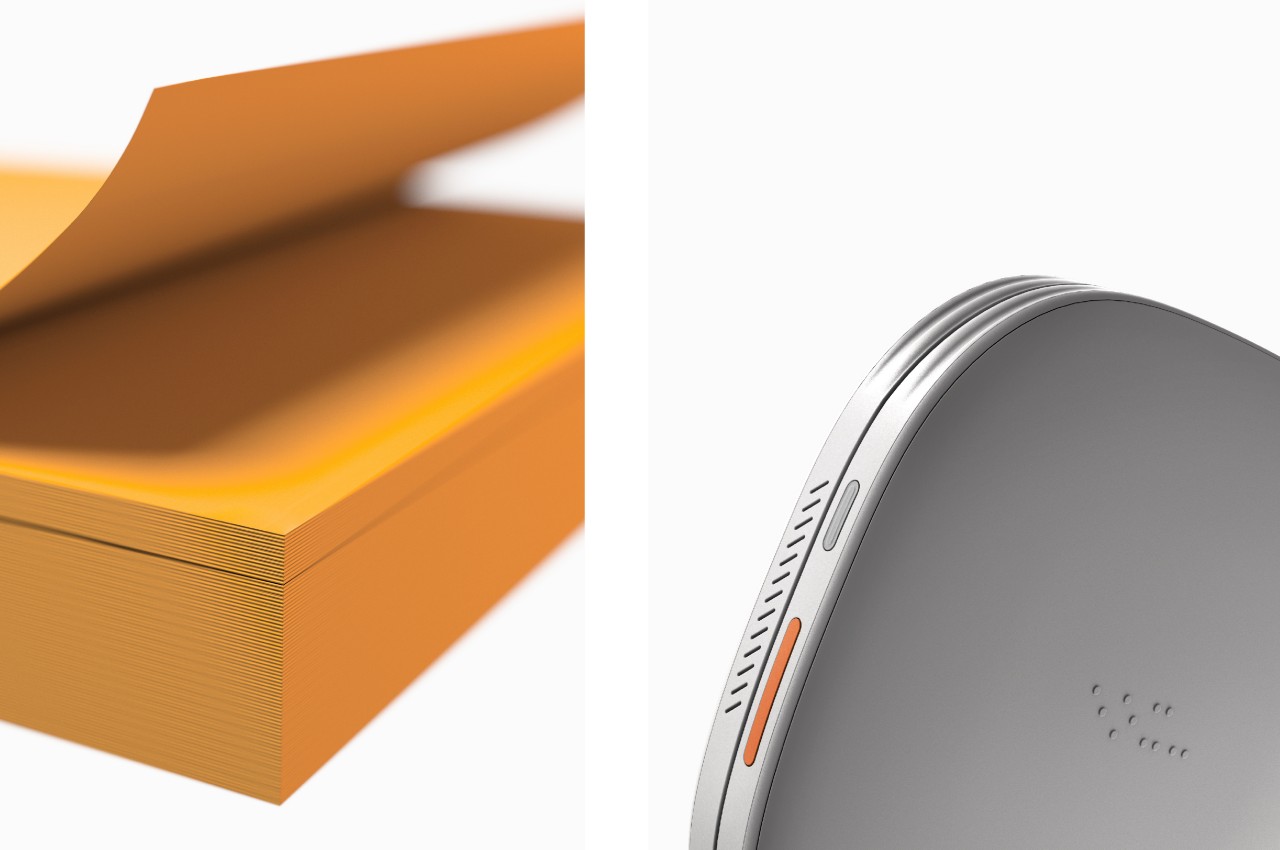

Many smart devices today tend to value aesthetics or functions too highly without considering how those would negatively impact the experience of people who are either blind or visually impaired. Some have too many buttons or have buttons that are all shaped similarly, making it difficult to tell by touch which one is which. Worse, there are those that use only touch controls on flat glass surfaces, which are completely useless unless you can see their marks. Beyond Sight is a collection of concept designs that address these flaws by using unambiguous motions and shapes that actually look fun to use, regardless of the state of your vision.

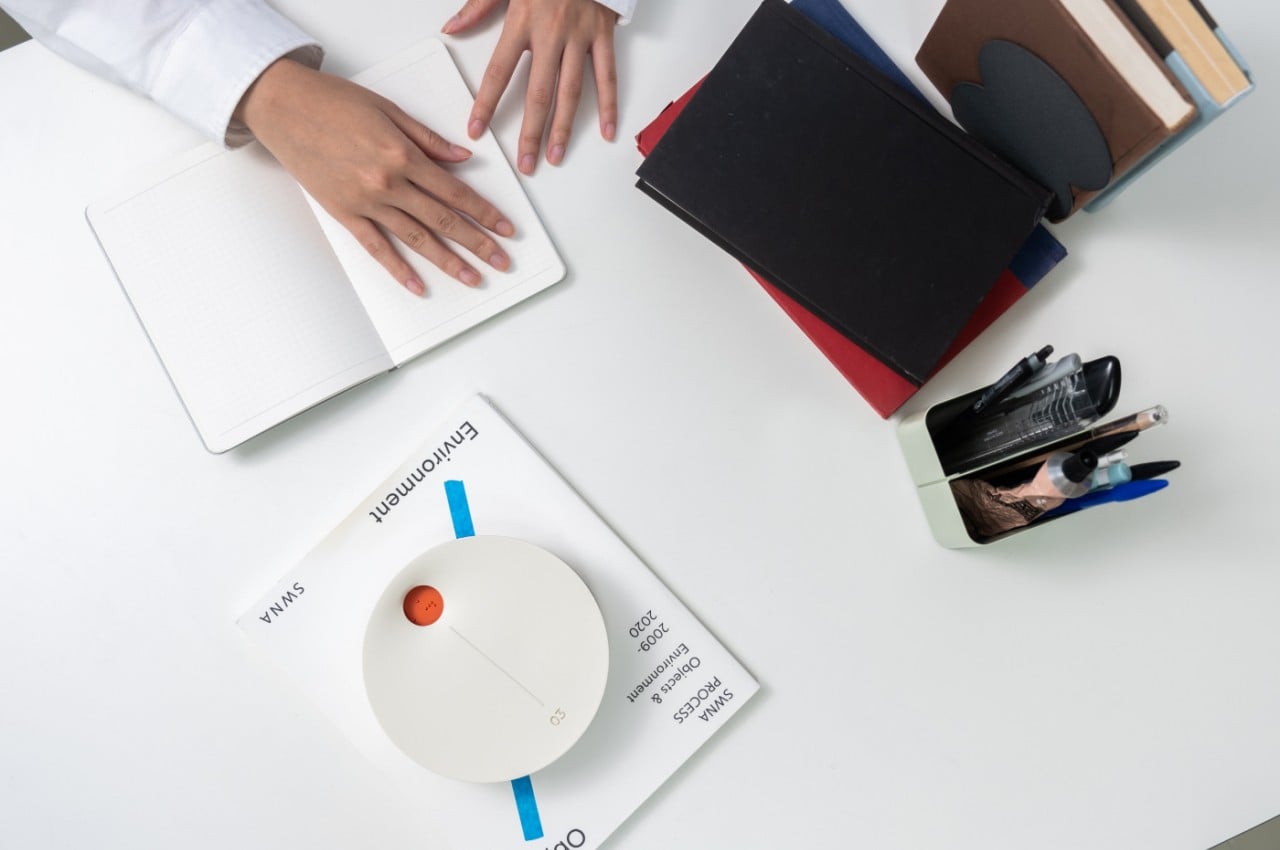

A smart speaker, for example, uses simple taps to play or pause the audio. Volume is controlled by sliding a ball up or down a pole while changing tracks involves turning the dial at the top. For people who can’t see or can’t see clearly, these definite tactile controls leave no room for guessing their functions. For those that can see what the speaker looks like, the design adds an element of fun and play to a device that has almost become too utilitarian these days.

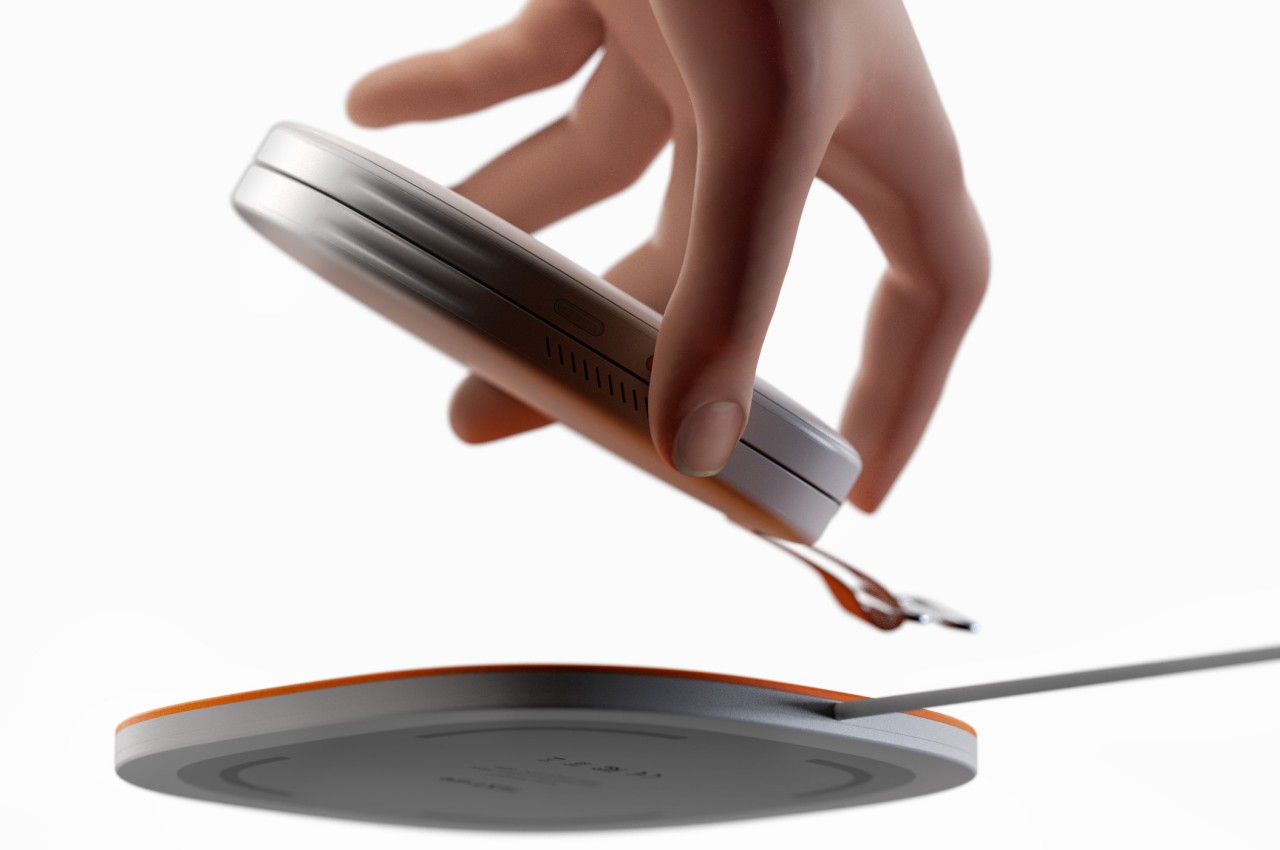

The smart remote control might look and feel like a toy flashlight, but its polygonal shaft does more than provide a good grip. To change channels, you roll the device to one or the other side. To turn the TV on, you simply put the remote down from a standing to a lying position. The head of the device is a dial that you can turn to adjust the volume, and a large button lets you summon your voice-controlled AI assistant to do the more advanced functions that the remote doesn’t support. Admittedly, the rolling gesture might be a bit cumbersome, especially if you need to go through many channels quickly.

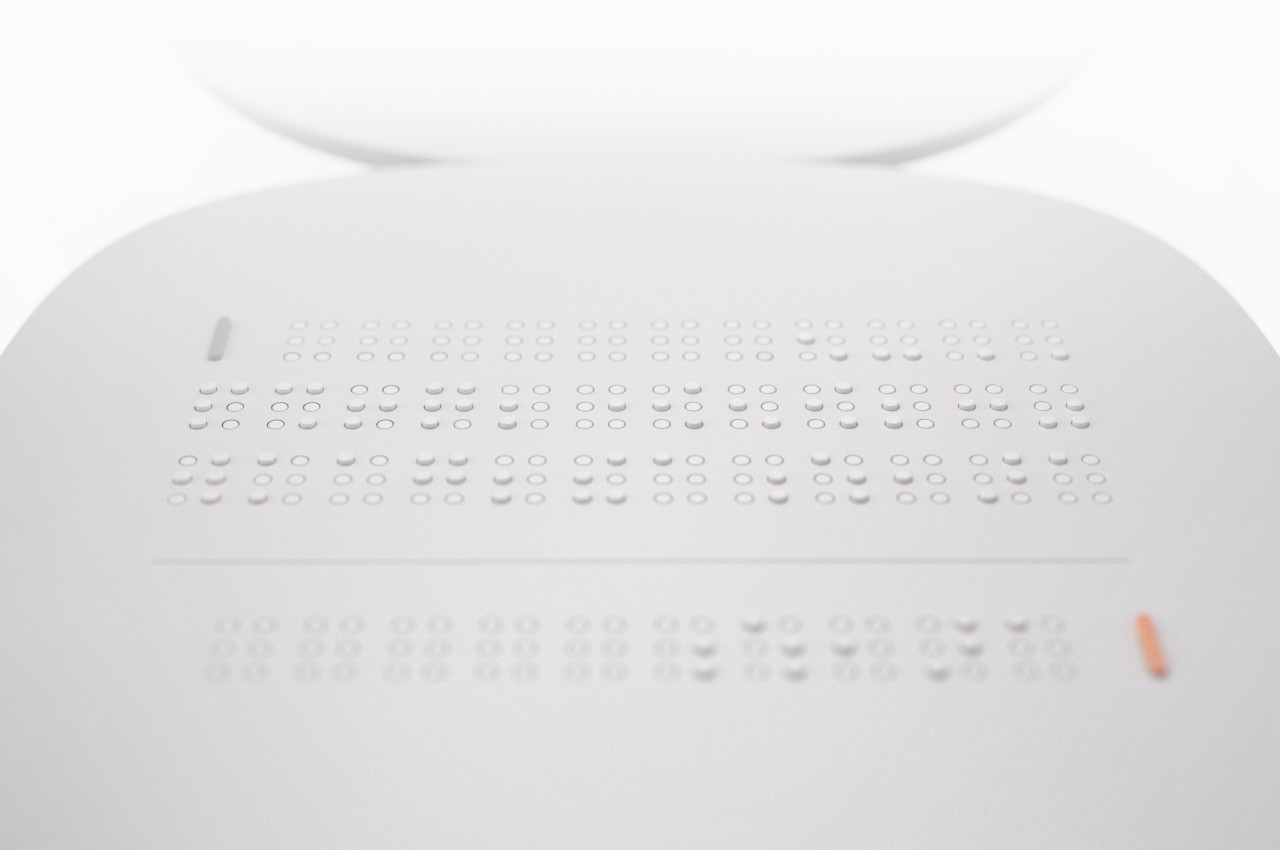

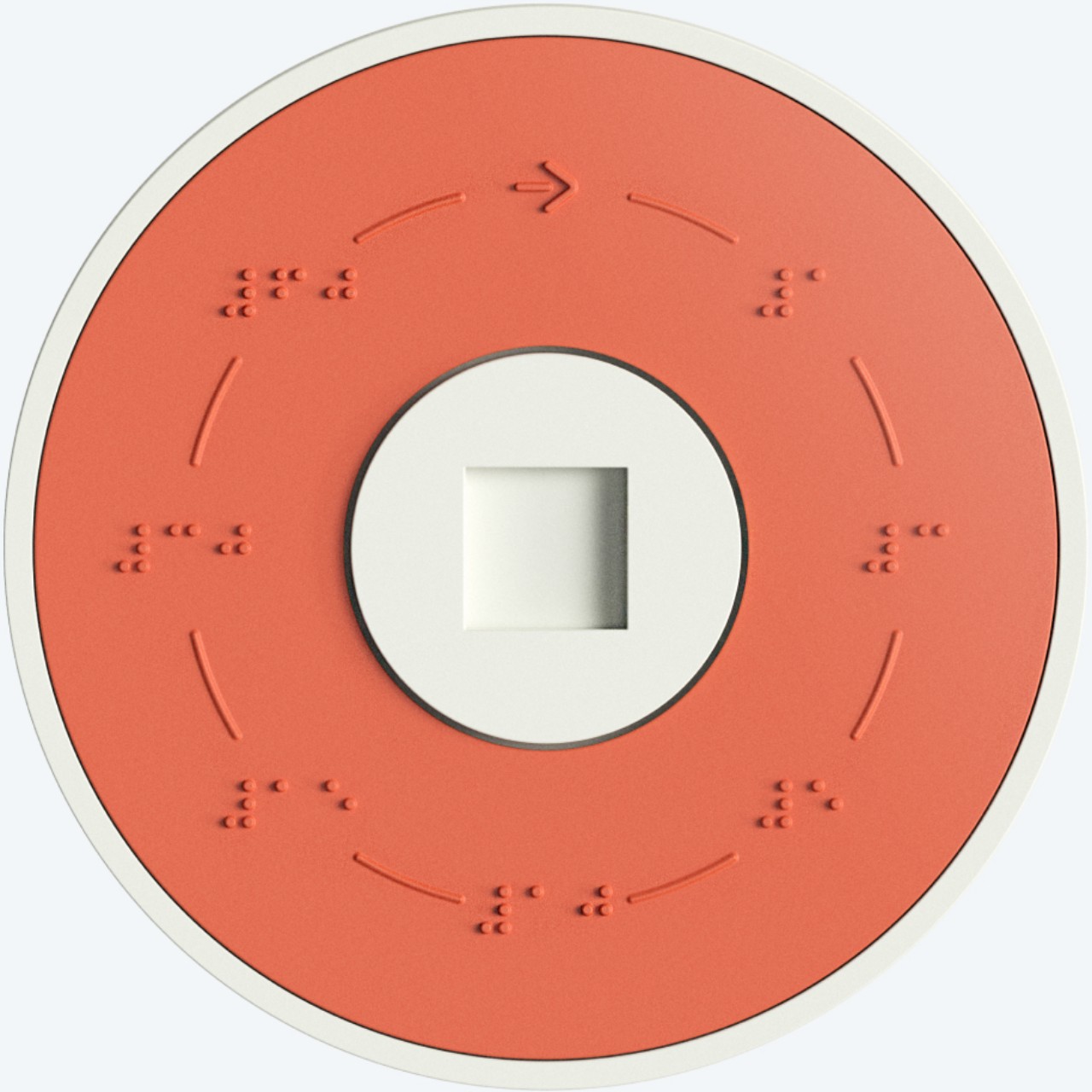

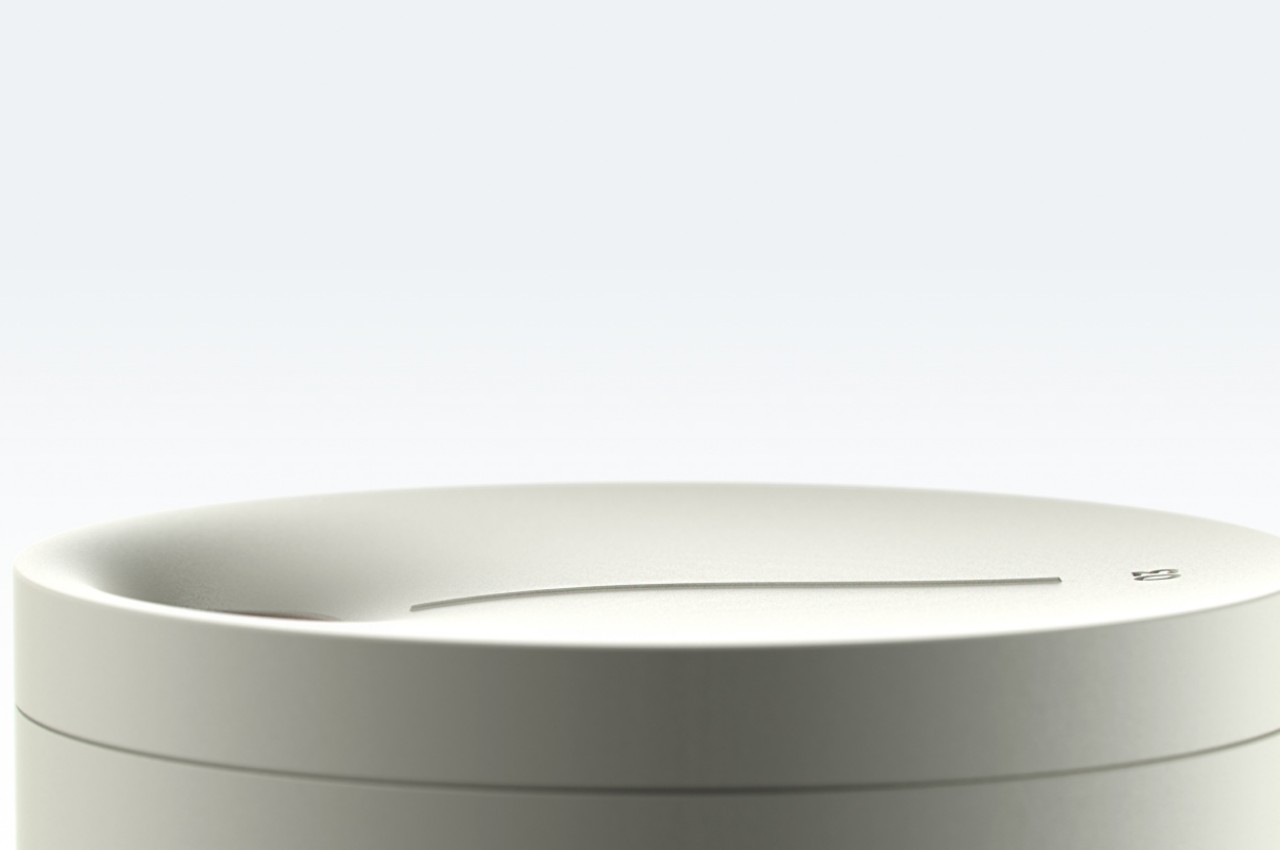

Lastly, a timer imitates the primary mechanism of rotary phone dials of the past so that people can slip their finger into the large hole and read the time in Braille. Setting the timer involves just turning that dial to the desired amount of time in 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 60-minute intervals. The circular surface of the device slopes down toward that hole, easily guiding the finger to where it needs to be.

For those with visual impairments, the designs of these concept devices give them enjoyment and security in a home that’s increasingly becoming impersonal and intimidating for them. For those that can see clearly, the devices’ designs give them a toy-like character that hints not only at their ease of use but also at their fun controls, proving that accessible designs can truly benefit everyone.

The post Smart home device concepts empower visually-impaired members of society first appeared on Yanko Design.