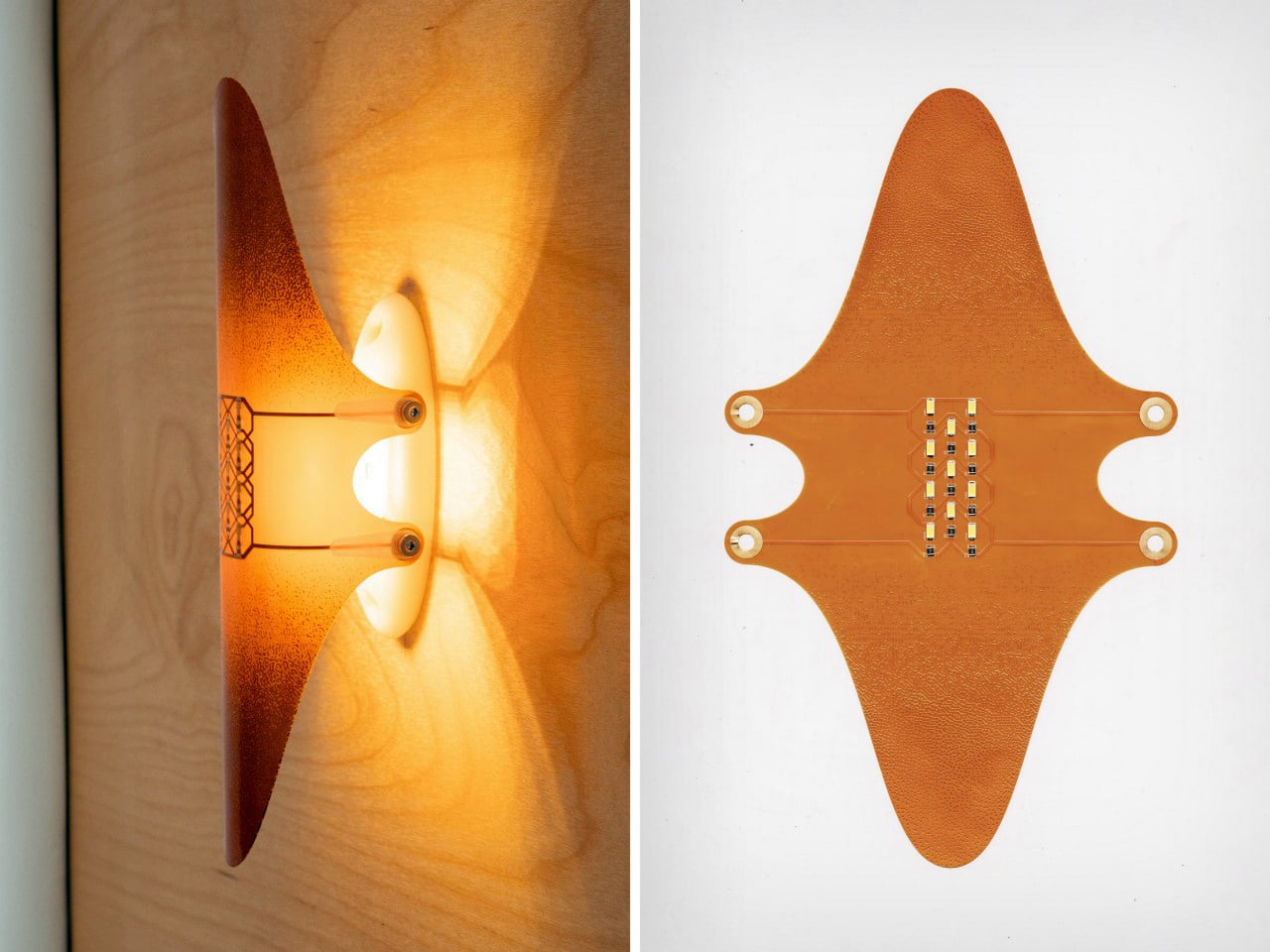

Most LED sconces are thin metal plates and diffusers, designed to disappear into a wall and quietly meet a lumen spec. That approach is efficient but rarely memorable. The Iris Sconce by Siemon & Salazar is the opposite, a fixture that leans into glass and bronze as expressive materials and treats light as something sculpted rather than simply emitted, turning a functional wall mount into a small piece of living craft.

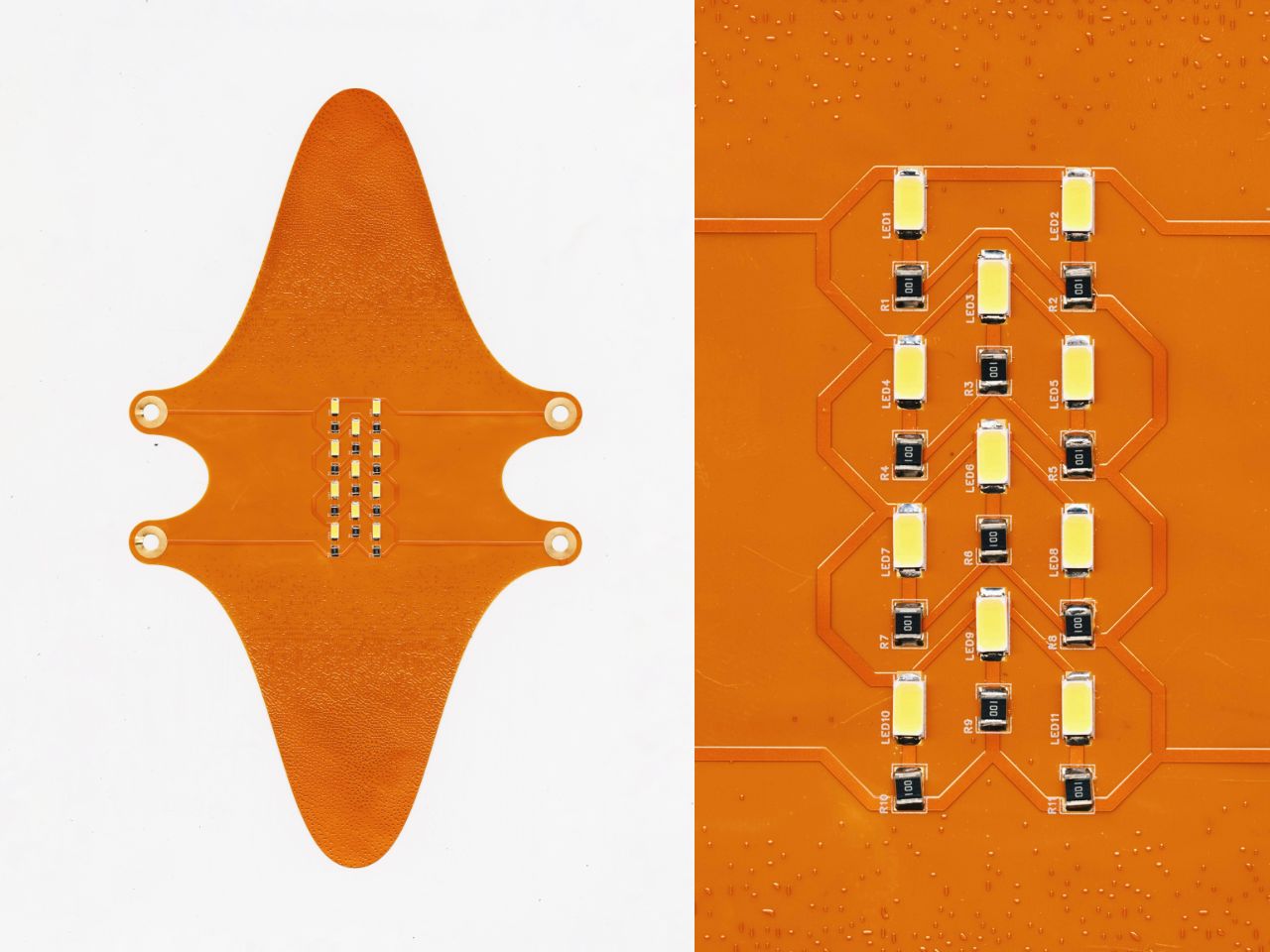

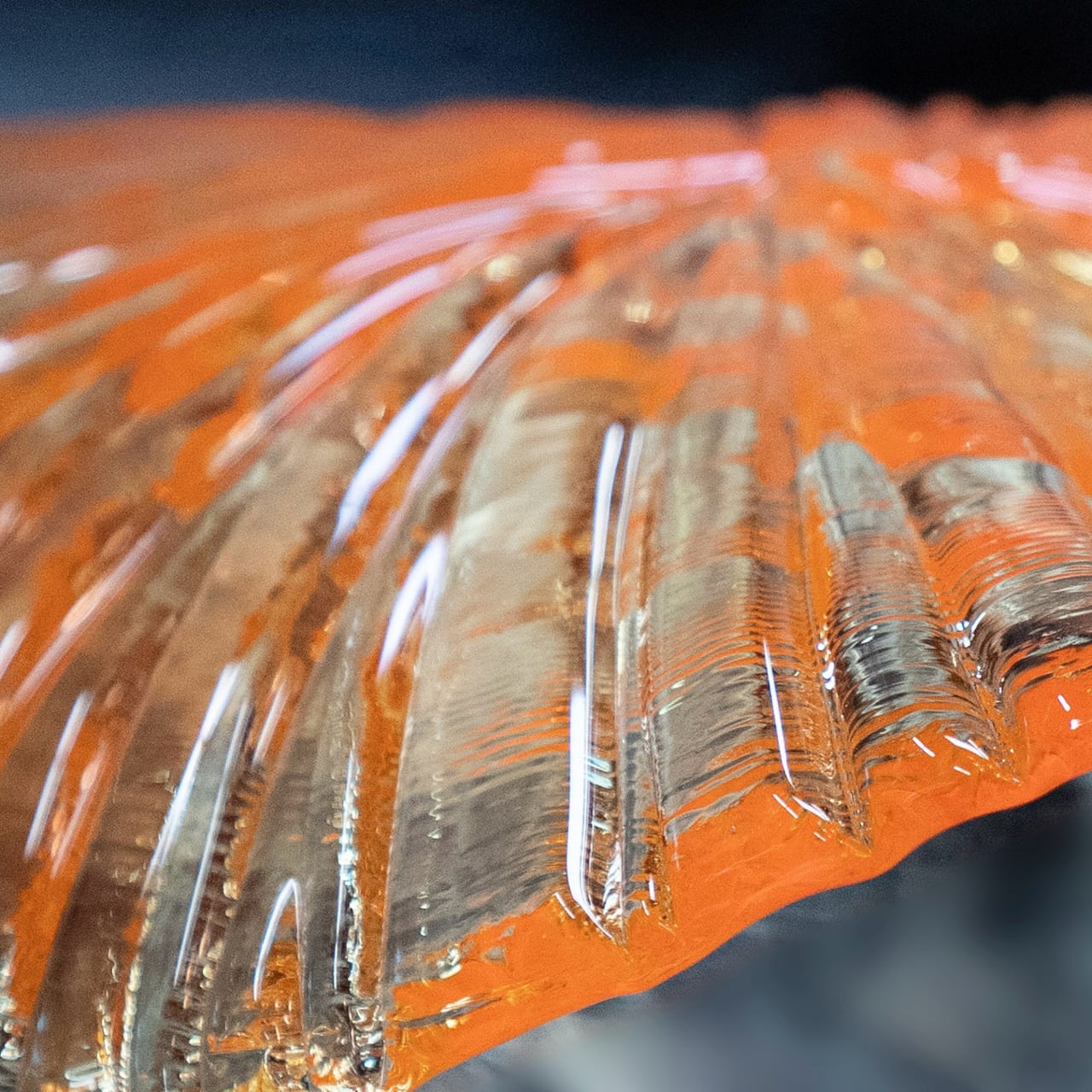

The studio describes Iris as a piece that uses mottled clear thick glass and a cast-bronze heat sink to balance ancient craft with a forward-looking spirit. Each sconce is shaped by hand, with molten crystal poured directly and manipulated immediately, so no molds are used and no two patterns are alike. The result is a fixture that feels more like a living object than a repeated product, where the character comes from the glass itself.

Designers: Caleb Siemon, Carmen Salazar

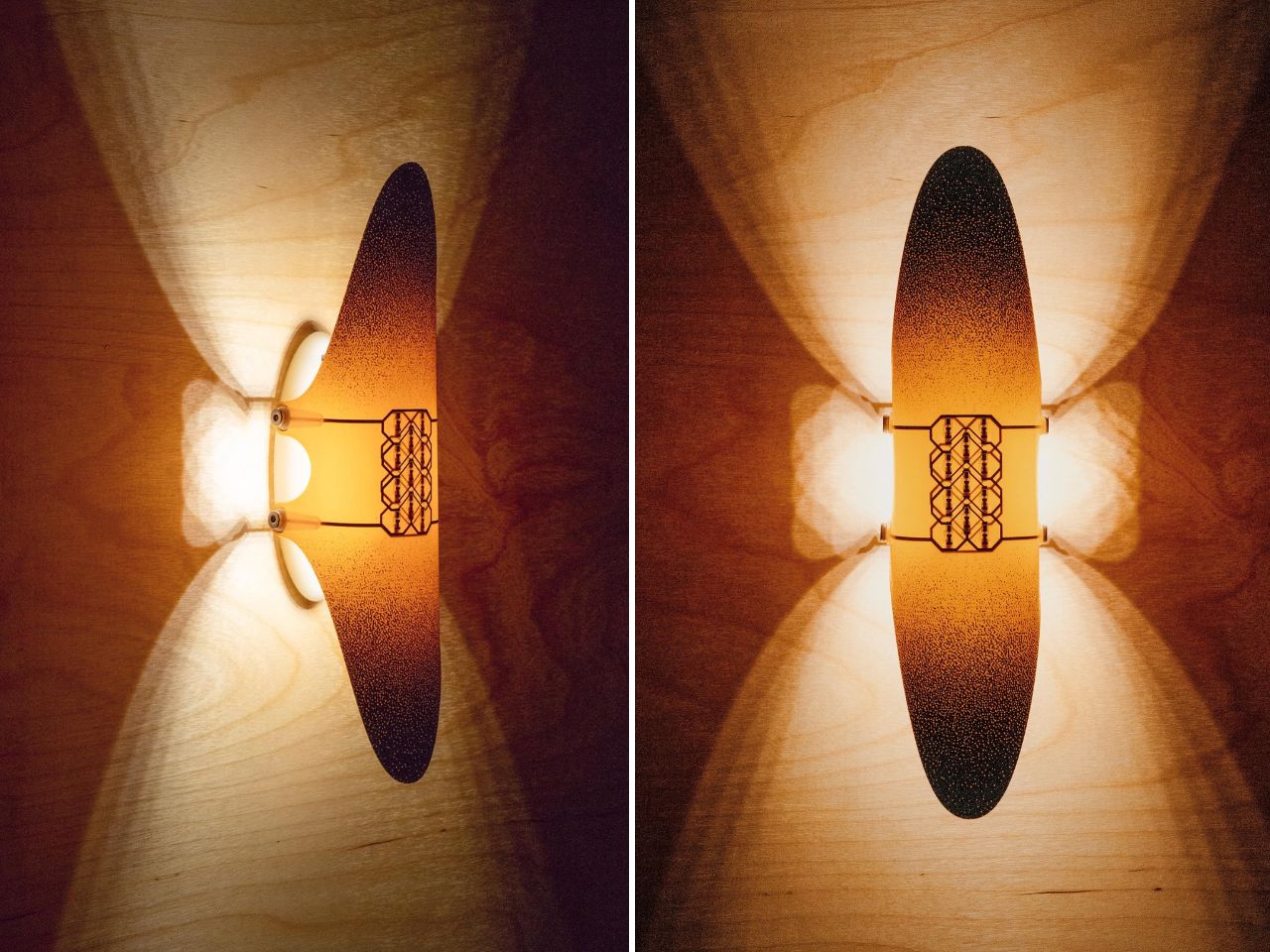

The glass is lead-free crystal that starts as a glowing pool poured from a crucible, then worked while still hot to create ripples, grooves, and thickness variations. That hot-forming process, without molds, means each disc has its own outline and internal weather. For a designer or homeowner, that translates into a wall of light where every piece has a slightly different voice, and where the surface feels more like water frozen mid-flow than a stamped shade.

The cast-bronze element at the center acts as both a heat sink for the LED and a visual anchor. Its rough, hammered surface contrasts with the smooth glass, and it reads like a pupil, a seed, or a small meteor embedded in crystal. The bronze conducts heat away from the LED, but it also brings warmth and weight to the composition, grounding the otherwise ethereal glass and giving the sconce a core you can read even from across the room.

The thick, textured glass behaves more like a lens than a shade, bending and scattering light into a halo on the wall. The LED sits behind the bronze center, so light spills around it into the glass and then out into the room as a corona of streaks and soft gradients. The effect is less about a beam and more about a field, turning a blank wall into part of the fixture itself.

Iris is sized to work as a single focal point above a mirror or as a series along a corridor, and it can be mounted on walls or ceilings. Because no molds are used, grouping several creates a field of related but non-identical eyes or flowers, which suits projects where lighting is meant to be seen. The integrated LED keeps the profile relatively shallow, and the bronze heat sink means the fixture can run for years without fading.

Iris reminds you that even a code-compliant LED fixture can carry the marks of molten glass and cast metal. Each sconce is genuinely unique, not just in finish but in shape and pattern. For people tired of flat panels and generic cylinders, it feels like a small argument for bringing a bit of studio craft back into the everyday act of turning on the lights, where every time you flip a switch, you are also lighting up a piece that was poured, shaped, and cooled into something one of a kind.

The post Iris Sconce: Hand-Shaped Glass Wall Light Where No Two Are Identical first appeared on Yanko Design.